The city-wide exhibit “El Cusco de Martín Chambi” was born out of the sudden sense of anachronism I experienced every time I was in Cusco and happened upon the street photographers whose presence dominates Plaza San Francisco in the heart of the city. They call attention to their trade by standing behind the imposing wooden tripods that formerly held the large format cameras in use in the early days of photography. Regardless of the weather, in summer and in winter, wind and rain, they can invariably be found sheltered by the church which overlooks the plaza. One day I asked Sr. Bernardo, who had been at the plaza for over 50 years and was known to everyone, to take a photograph of my husband and me. He proceeded to pull out a little digital camera from the box perched on top of the tripod and walked us down the incline to a small wall where he asked us to pose. With the church at our back, he took our photo, grabbed his cane, and slowly and laboriously made his way to a copy shop. When he returned, he charged us 10 soles ($3 USD) for a 5 x 7 print. Around that same time, I came across the stunning catalogue Martín Chambi. Photographs, 1920-1950 published by the Smithsonian. The contrast between the quality of the photograph Sr. Bernardo had taken of us and those of Cusco’s world-renowned indigenous photographer could not have explained more eloquently the reasons why street photographers on Plaza San Francisco reference that traditional practice despite the waning of glass plate photography long ago. Intrigued, I started to delve into the history of Andean photography and slowly made my way into many of Cusco’s photography archives. Out of the Archive and Into the Streets is a reflection of these experiences and my growing conviction that we need to honor the gesture of the street photographers like Sr. Bernardo who can only afford to work with the smallest digital cameras, even as they signal the greatness of the photographic era that came before them, standing by the large wooden tripods used when photography first arrived in the Andes.

My incursion into many of Cusco’s archives made me realize very quickly that there is a healthy equilibrium that allows an archive to live up to what I came to think of as its full potential. That full potential comes about when an archive is housed in a safe place, is on the way to being well preserved, and is open to and in dialogue with the present. This is especially important in Cusco because elders still may remember many of the subjects and events photographed. With their passing, that memoria will be lost. The need to protect and preserve, then, must be balanced with the imperative to exhibit.

Sadly, many archives often exist in precarious situations or not at all. Miguel Chani (1860-1951), for example, is credited as the founder of what came to be known as the Cusco School of Photography, but there is no Chani archive. An indigenous photographer, he established several successful photography studios across the southern Peruvian Andes in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. As happened often at the time, when he lost his fortune in 1920, his studio on Calle Marquez in Cusco was taken over by two other photographers who became internationally renowned: first, Juan Manuel Figueroa Aznar, and later Martín Chambi. These studios most likely absorbed some of Chani’s photographs, while others ended up in private collections. Along with other great photographers such as José Gabriel González and the Cabrera brothers (Filiberto and Crisanto Cabrera), who all worked in Cusco in the early to mid 20th century, Chani started documenting the profound transformation the city began to undergo with the arrival of the first railway in 1908 and trams and electricity in 1914—in short, modernization and the dreams of greater prosperity for all that came along with it. The designation “Cusco School of Photography” signals the cultural and social effervescence which took place at the time; it celebrates the great visual archive that these early photographers helped establish and that street photographers continue to reference today.

Unfortunately, until recently, many of the glass plate photographs of the late 1800s and early 1900s, which today are considered invaluable documentation of a city that grew from a small enclave to the archeological capital of Latin America, were simply sold piecemeal for a pittance in Cusco’s Sunday bazaar. This valuing of photography only happened after Martín Chambi gained worldwide recognition in the 1970s. By then it was often too late for many collections in the city which had been dispersed. Elsewhere across Peru, collectors continue to comb flea markets and garbage dumps in search of disposed photograph collections. Juan Mendoza, a retired engineer and the son of a contemporary photographer of Chambi’s in Cusco, recently found five fabulous early photographs in Lima’s (in)famous “thieves’ market” where he goes weekly in search of these “treasures” that others discard mistaking them for trash.

Archives can become ghostly presences when they exist in the midst of the daily bustle of a city but remain isolated and accessible to only a select few academics and cognoscenti.

Indeed, few archives have survived the many destructive forces at work in Peru. Lack of understanding of the value of a collection most often leads to the dissolution of an archive. Contrary to expectations, however, the overvaluation of an archive has a similar effect. Once the value of glass plate photography was understood, the collections were so treasured that people fought over their possession. Many were torn apart by family feuds or rendered inaccessible and therefore un-usable as a public commons. Many archives therefore simply exist as potential archives—that is, collections we know about but that do not come into their own. In other words, they do not exist. The archive of Eulogio Nishiyama is a prime example. A famous Japanese-Peruvian photographer, he was a cameraman and also cinematographer who, with Luis Figueroa, co-directed Kukuli (1961), the first film in Quechua. Because Nishiyama did not leave a will, ownership of the 80,000 photographs in his archive has been fought over by the family since his death in 1996. Nishiyama’s son in Cusco has part of the collection and has done the most to promote his father’s work, organizing exhibitions and publishing several catalogues. His other siblings have the other parts of the collection, and it is not known in what state they are preserved, if at all. Also contributing to the precarity of the collection, Carlos Nishiyama lives in a humble basement on the side of a steep hillside on Calle Choquechaca in Cusco. When I visited him, I wondered what would happen to the collection in a big storm since damage from flooding had largely destroyed the collection of Sr. Bernardo—one of the San Francisco cathedral street photographers. After water came down the mountain into his house, all that was left of his over 50-year collection were a couple of shoe boxes full of largely damaged photographs.

Distrust of the government also plays a large role in the dispersion of important Andean archives. I was shocked, for example, to see a part of Juan Manuel Figueroa Aznar’s collection of glass plates from the early twentieth century in a trunk on the floor of the humble apartment of his son. An artist who fought his way into Cusco’s closed elite, Figueroa Aznar, like many others, started out working in Arequipa at the renowned studio of Max T. Vargas in 1903-04 and then also that of the Vargas brothers. He first became known in Cusco for his highly artistic foto-óleos or illuminated photographs. Leaving this technique of artistic photoshop avant la lettre behind, he went on to become one of the city’s greatest photographers. Two of his most known photographs are series of staged photographs that tell a humorous story and feature the photographer as actor: one is of a jilted lover and another of a dandy who successfully seduces a nun, with visible consequences 9 months later. He took this photograph of his wife, Ubaldina Yábar, Luis Figueroa’s mother, in one of the haciendas her family owned in the town of Paucartambo. Having married into one of Cusco’s most distinguished families, Figueroa Aznar portrays his wife dressed in all her finery, as if on her way to Sunday mass or an important social gathering, astride a horse in the courtyard. Two figures, much more humbly attired, look down on this scene from the balcony and only highlight his wife’s elegance.

An intellectual and politician, Figueroa Aznar was also part of the “calaveras”—a group of pranksters in Cusco’s elite who made social statements in highly performative ways. In the recollection of his son, filmmaker Luis Figueroa, the “calaveras” managed to draw attention to Cusco’s unsanitary conditions one weekend by planting little Peruvian flags on the mounds of poop left in Plaza San Francisco after the weekly market, thus shaming the mayor into fighting for sanitary reform in the city.

Figueroa Aznar’s incredible glass plate collection had thankfully been preserved by Cusco’s dry weather, which acts like a natural air conditioner. While some of the glass plates had fortunately come into the famous holdings of the Fototeca Andina, and some are in private collections, Luis Figueroa valued his father’s work and wanted to hold on to what he still had in his possession, however fragile his circumstances, rather than donate anything to public institutions of which he was profoundly mistrustful. The son’s distrust is understandable given centuries of systematic plunder of the area’s natural resources and archeological treasures by foreign collectors, by the central government, and by the Ministry of Culture itself. Thankfully, shortly before his death the Bienal de Fotografía de Lima Gustavo Buntix curated a great exhibit of Figueroa Aznar’s works and in 2012 his niece, Ximena Figueroa, managed to create an archive buying all the glass plates and cleaning and cataloguing them with the help of Mexican conservationist Cecilia Salgado. The archive is now in finally safe in a temperature-controlled room in her home in Barranco, Lima. While many collections, then, are destroyed by their owner’s overzealous protectiveness, others disappear because of the owner’s oftentimes extremely precarious financial situations, and still others are lost and dispersed simply because their value is not understood.

Archives can become ghostly presences when they exist in the midst of the daily bustle of a city but remain isolated and accessible to only a select few academics and cognoscenti. The Martín Chambi Archive is a case in point. Thankfully, it was considered irreplaceable by Chambi’s children, Víctor and Julia Chambi, and his grandson Teo Allaín, and was on its way to being fully preserved. It is also a space that welcomed researchers from all over the world. However, I only discovered its location thanks to French anthropologist Jean-Jacques Decoster who gave me the director’s private telephone number. I contacted Teo Allaín Chambi, grandson of the great photographer, and he invited me to the archive. When I first visited it in 2012 it was housed in proximity to the university but lacked any outward sign of its existence. Since then, it has been relocated to a basement apartment in a new building in Cusco’s Distrito Empresarial, but again there is no sign posted to advertise its existence. When I asked Teo about this he responded that the cloak of anonymity was as affordable and effective an anti-theft system as any. However, while the strategy of invisibility had perhaps protected the archive, we must keep in mind Jacques Derrida’s positing that there is no archive “without an outside.” And Cusco and its people and their memory of the period in which Martín Chambi lived and worked is definitely the first “outside” of his archive.

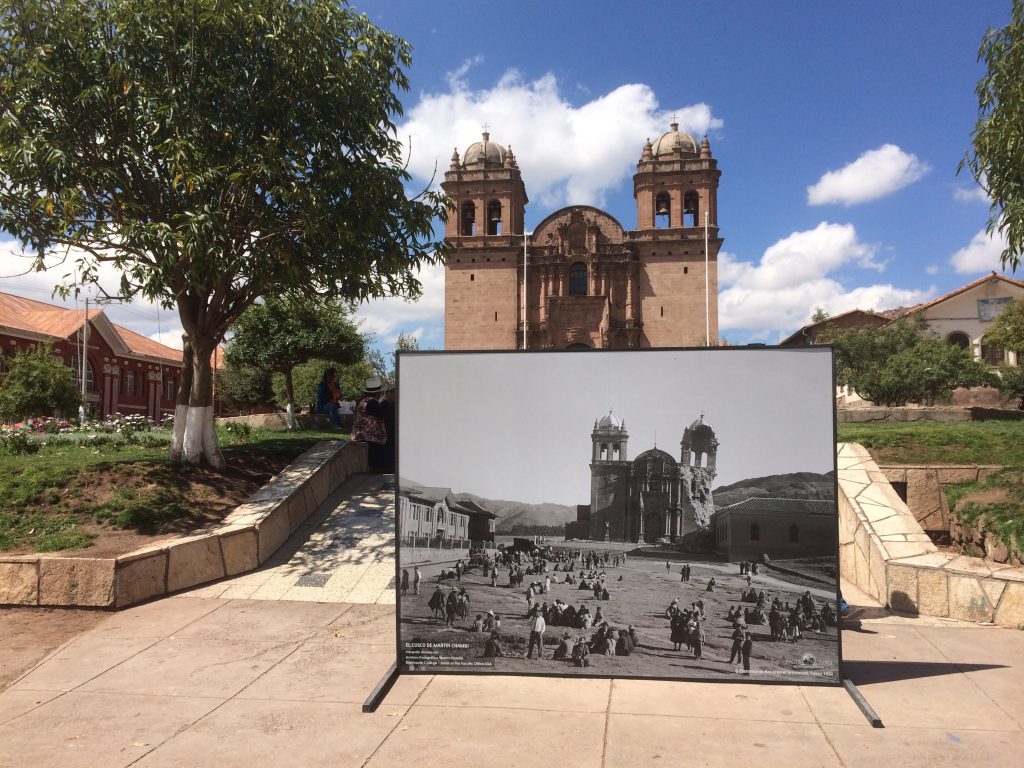

As a way to open it to the city, I proposed to Teo that we collaborate to continue digitizing the smaller glass plate negatives and at the same time curate a city-wide exhibition of Chambi’s photographs of Cusco. After several brainstorming sessions and trips back and forth between Cusco and Hanover, NH, we settled on enlarging 32 photographs Chambi had taken in the streets of Cusco until the late 1950s. “El Cusco de Martín Chambi” came about in this way, and the exhibit was up in the streets during September-October 2014. Almost one hundred years after he took the photographs, then, we turned Chambi’s lens back onto the city he had loved, photographed, and made known worldwide. When “El Cusco de Martín Chambi” came down, Teo summarized the effect of the exhibit apodictically: “Rompió el ojo” (It broke the eye), as if to imply that the exhibit had unveiled Cusco to its inhabitants and forced them to see their city anew. [See section 5, “Out of the Archives and Into the Streets”].