Era una masa informe, ahistórica…Era un pueblo de piedra. Así estaba de inerte y mudo; había olvidado su historia..”

[They were a shapeless, ahistorical mass…a people of stone. They were inert and mute; they had forgotten their history..]

—Luis E. Valcárcel, “Tempestad en los Andes,” Revista Amauta 1, no. 1 (1926): 2.

La nueva generación peruana siente y sabe que el progreso del Perú será ficticio, o por lo menos no será peruano, mientras no constituya la obra y no signifique el bienestar de la masa peruana que en sus cuatro quintas partes es indígena y campesina. Este mismo movimiento se manifiesta en el arte y en la literatura nacionales en los cuales se nota una creciente revalorización de las formas y asuntos autóctonos, antes depreciados por el predominio de un espíritu y una mentalidad coloniales españolas.

[The new generation feels and knows that Peruvian progress will be fictitious, or at least will not be Peruvian, as long as its work does not contribute to the welfare of the Peruvian people, which is four-fifths Indigenous and peasant. This same trend is evident in art and in national literature in which there is a growing appreciation of Indigenous forms and affairs, which beforehand had been depreciated by the dominance of a Spanish colonial spirit and mentality.]

—José Carlos Mariátegui, “On the indigenous problem,” 1928.

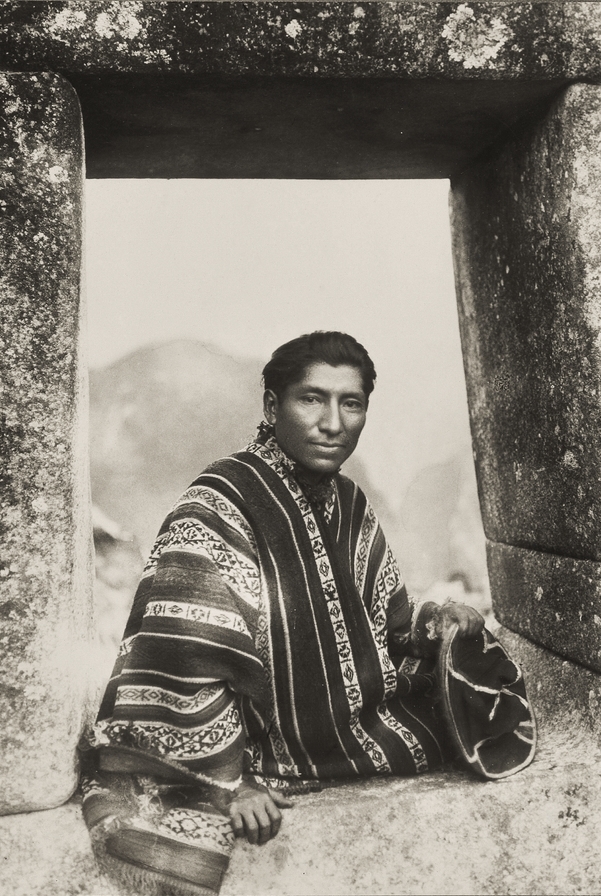

Unlike his famous self-portrait of 1923 where Chambi had on the formal suit and tie he invariably wore in Cusco as a sign of his status as a successful professional, in the above self-portrait taken a few years later, he proudly wears a poncho. He poses in the frame of one of the famous trapezoidal windows at Machu Picchu before which Ricarda Luna and his friends had danced. This self-portrait at Machu Picchu shows Chambi as a Quechua subject strategically underlining his indigeneity to validate his claim to the ruins. One can almost hear him proudly saying, “this is mine.” Is this 1930 self-portrait a performance of indigeneity? I asked myself this question, reminded of the many conversations around indigeneity I had had with anthropologist Antuca Vega at the Fototeca, and in particular her category “disfrazados.”

Chambi’s gesture is quite radical, particularly when viewed within the larger frame of the emergence of the indigenista movement in the early 20th century. In Lima, the indigenistas famously tried to grapple with what at the time was called “the problem of the Indian”; namely, how to integrate the vast majority of the population who were Indian, seen as “backward” and semi-civilized people, into modernity and the nation. The question was raised by Manuel González Prada in a 1904 essay entitled “Nuestros indios,” where he proposed to use education and literacy campaigns to integrate, that is acculturate, Peru’s largely indigenous population. It is not incidental that this proposition emerged at a time when the idea of Peru was reduced to Lima, and Lima was dominated by a colonial mentality that prided itself on being creole; that is, non-Indian. One can only imagine how offensive and jarring it must have felt for an indigenous photographer like Chambi and his peers in the intellectual circles he frequented in Cusco to hear his existence and culture discussed as a “problem” on the national stage; and perhaps even worse, to be reduced to the patronizing “our Indians.” I would like to suggest that this sense of outrage and perhaps wounded pride was the driver at the heart of the potent indigenist movement that emerged in Cusco at the time. Indeed, while “indigenismo” serves as an umbrella term for the multifaceted approaches to the problem of creating national belonging across Latin America in highly heterogeneous societies in the early twentieth century, one could and should distinguish between Lima’s indigenistas (mostly mestizos for whom indigenous people were an abstraction) and Cusco’s indigenistas who were local, often indigenous, and who attempted to represent indigeneity in all its complexity; they valorized it, and they succeeded in mobilizing it to force the nation to re-frame the conversation around race and culture for decades to come.

One can only imagine how offensive and jarring it must have felt for an indigenous photographer like Chambi and his peers in the intellectual circles he frequented in Cusco to hear his existence and culture discussed as a “problem” on the national stage; and perhaps even worse, to be reduced to the patronizing “our Indians.”

In Cusco, anthropologist and historian Luis E. Valcárcel in his seminal Tempestad en los Andes (1927) started out bemoaning the backwardness (literally the “stone age,” as we see in the epigraph) to which indigenous peoples had been condemned since the conquest. He refused the colonial paradigm of barbaric “Indians” frozen in time and instead went on to radically argue that indigenous peoples could once again attain their former greatness. Indeed, he poetically anticipated—and perhaps helped call forth—a “thawing” in the Andes, an approaching cosmic storm, a renaissance. Cassandra-like, he foresees that “culture will once again descend from the Andes” [la cultura bajará otra vez de los Andes]. Indeed, in Cusco indigenismo‘s roots can already be traced as far back as Inca Garcilaso de la Vega and his famous Comentarios Reales de los Incas, published in Lisbon in 1609. Based on stories Garcilaso had been told by his Inca relatives when he was a child, the Comentarios contain descriptions of Inca life, with a second part published in 1617 devoted to the Spanish conquest of Peru. Centuries later, the radical writings of Clorinda Matto de Turner, in particular her anticlerical manifesto, Aves sin nido, (1890), denounced the oppression of Indians and specifically the Church’s abuses in Cusco. Both Matto de Turner and Inca Garcilaso’s writings were censored, and Matto de Turner was forced into exile. Joining hands across the centuries, these figures laid the groundwork for the emergence of a strong indigenista movement in Cusco in their advocacy for indigenous rights, their highlighting of government and church abuses, and their support for interracial relations in a segregated caste society. Straddling Lima and the Andes, writer and ethnographer José María Arguedas created a magnificent body of stories and novels such as Yawar Fiesta (1941), Los ríos profundos (1958), Todas las sangres (1964), and El zorro de arriba y el zorro de abajo (197), written in a new, invented, hybrid language through which Arguedas tried to encompass todas las sangres.

The term indigenismo, then, is a catch-all for the intense creativity and intellectual effervescence that characterized the late 19th to mid 20th century across Latin America. As a political movement, indigenismo would advocate for equal citizenship rights and land reform (that is, the return of native lands to native peoples). As a recent documentary (La revolución y la tierra, 2019) argues, the early twentieth century multipronged cultural and political fight against the oppression of Indians culminated in the agrarian reform effected by left-wing Peruvian General Juan Velasco Alvarado in 1969, along with the decree that campesino should henceforth replace the term “Indian,” which the regime considered degrading. But indigenismo would not have had the far-reaching effect it still has today had it not also been, simultaneously, a fight for equality in the visual field. Cusco’s School of Photography was a key player in the indigenista movement’s production of a new image world and representations of indigenous peoples that were much more personal and dignified than those which heretofore had pervaded the anthropological lens. Indeed, modern Peru would be unthinkable without Cusco’s indigenismo and the questioning and reconstruction of the national identity inflected by an Andean sensibility that it brought about in the culture at large.

Despite the importance of literary and political writings, indigenismo would perhaps be less well known today, then, had it not been accompanied by the emergence of what could be called a visual indigenismo. José Sabogal, one of Peru’s most famous artists, created one of the earliest stylized portraits of indigeneity. Exemplifying the new global networks that were coming into being thanks to improved communication between Cusco and Buenos Aires, Sabogal had temporarily settled in Cusco after having studied art in Buenos Aires where pre-Hispanic archeology had begun to inspire architecture, art, and fashion. In Cusco he created his “Alcalde Varayoc,” perhaps his most famous painting. Like most indigenistas he was not indigenous himself and thus, unlike Chambi, never moved away from representing Andean culture in an idealized and stylized form.

Nevertheless, his paintings contributed to profoundly alter the Peruvian national imaginary. He noted that in Lima, the capital city, there was no interest whatsoever in anything indigenous; the creole elite’s mentality was completely subservient to everything European. When he exhibited his indigenista Cusco-inspired paintings there in 1919, they were received as if from an exotic country. José Carlos Mariátegui, in the epigraph, echoes Sabogal’s lament almost 10 years later. Despite the persistence of profound forms of racism in Peru, it could be argued that this first incursion into a celebratory, indigenously-inspired painting tradition like Chambi’s “Indian and llama/Soledad del indio” paved the way for the reception of the indigenista performative and visual archive that was being created in Cusco and elsewhere at the time.

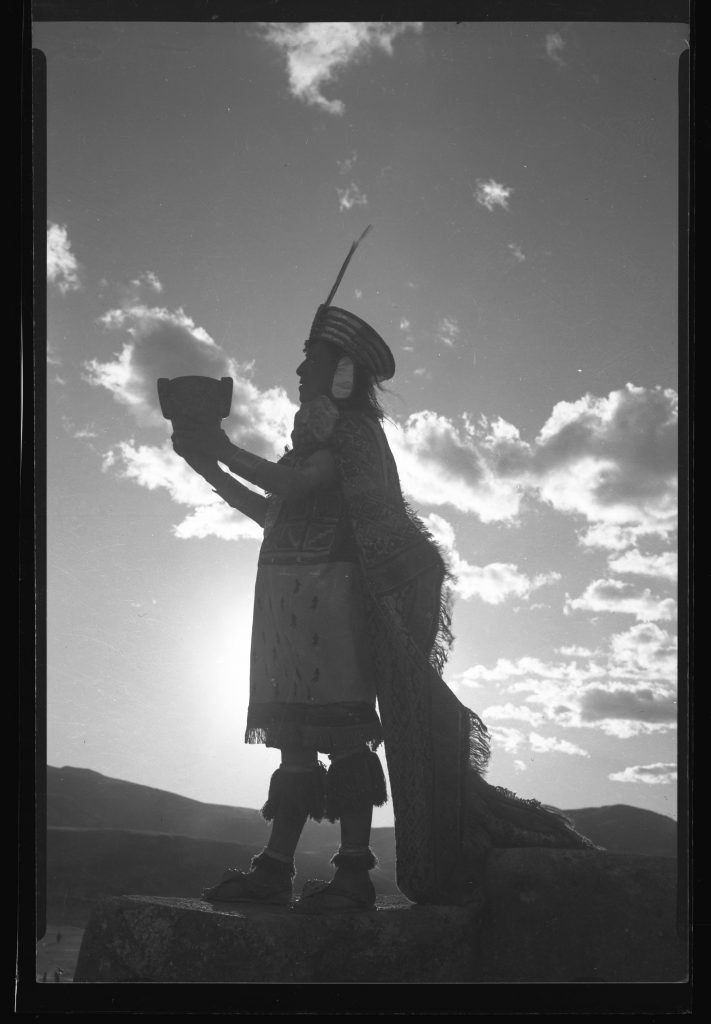

Chambi was instrumental in creating this new visual field, and his self-portrait with a poncho at Machu Picchu perhaps best embodies his strategy of affirming indigeneity and modernity in all its radicalness. Indeed, an indigenous indigenista, Chambi dedicated his life to making the city and its monumental archeological past known worldwide. His postcards typically are of views from on high of Machu Picchu and other ruins, and also included the now iconic backlit Indian with his llama that circled the globe. He made his living selling these to the tourists who were beginning to arrive in Cusco. Chambi’s photographs of Cusco’s archeological monuments were featured in many magazines in Cusco and Lima (Variedades, La Crónica). They were also in high demand in Argentina and Chile, where their publication contributed to making the “Inca” an architectural and artistic conceit. But Chambi also, at the same time, worked tirelessly to chronicle daily life in the city. This dual approach shows how savvy he was at marketing his photographs for different audiences. Thus, while his studio photography can be quite personal and even intimate, in the famous postcard of the backlit Indian and his llama, he transformed a campesino into a symbol of indigeneity legible worldwide. His many views of Machu Picchu have become iconic and instantly recognizable. While he too, like most Cusco indigenistas, viewed himself as a cultural ambassador, he also saw himself as indigenous and thus the “representative of his race.” As such, he sought to make that “race” visible. Criticized by Uriel García for his refusal to mobilize photography as a tool to denounce the oppression of Indians, he instead chose to use his lens to dignify a people until then dismissed as barbarous and abject, mere vestiges of the past. That is the gesture he embodies in his self-portrait with the poncho.

Chambi was instrumental in creating this new visual field, and his self-portrait with a poncho at Machu Picchu perhaps best embodies his strategy of affirming indigeneity and modernity in all its radicalness.

While Chambi’s archive is an important document of a key period in the Southern Peruvian Andes, it has to be seen as part of the larger archival impetus that emerged in the city during his lifetime. Working together across multiple fronts, indigenista photographers, local scientists, historians, artists, and intellectuals founded countless cultural and scientific institutes, newspapers, journals, and radio stations. They also established important archeological artifact collections to preserve and promote the pre-Columbian cultural heritage of the city and environs. They understood the dictum that political power depends on the control of the archive, which is also that of memory, as Jacques Derrida noted.

Working on multiple fronts (social, political, artistic) the indigenistas refused the colonial narrative of Spanish/European superiority and fought to affirm native and local identities. The discovery of Machu Picchu was key in both inspiring and buttressing their efforts. Unremarkable in and of itself because these ruins had long been known to locals, as I noted above, the “discovery” actually became important thanks to the savvy propagandistic efforts undertaken by Philadelphia-born economist and university reformer, Albert Giesecke. Brought to Cusco to settle massive student protests in Cusco’s prestigious Universidad Nacional San Antonio Abad, Giesecke very quickly understood the importance of center-staging local epistemologies as well as promoting key archeological discoveries abroad. As a result, the 1933 Congress of Americanists declared Cusco the Archaeological Capital of the Americas, and UNESCO designated the city a World Heritage Site fifty years later.

Important motors of university reform, such as Luis E. Valcárcel and Uriel García (who wrote the first doctoral thesis on an indigenous subject at San Antonio Abad University in Cusco, El arte Incaíco, 1912), very quickly understood the power of culture to draw the national imaginary away from its almost exclusive focus on Lima. Valcárcel’s trajectory is exemplary of the reach of Cusco’s intellectuals on the national scene. A key player in the university revolt that led to the most important reform undertaken to date, alongside his well-known writings discussed above, he founded Cusco’s archeological museum at the university in 1923. From there his trajectory only ascended: he went on to teach at the Universidad Mayor de San Marcos in Lima, to serve as Dean of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences, to found the Institute of Ethnology, to become Minister of Public Education (1945-47), and shortly thereafter to direct Peru’s Indigenista Institute. These important public posts allowed his indigenista agenda to have a national impact.

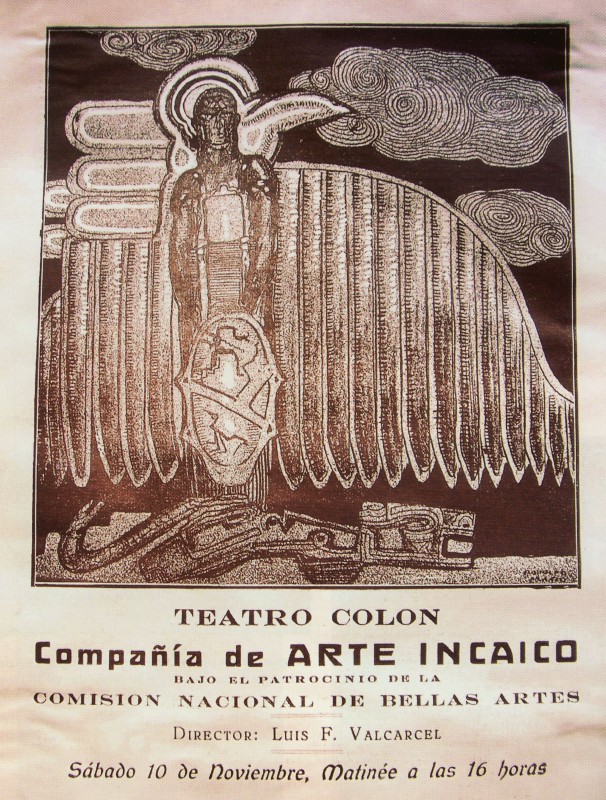

Inspired by this Andean-inflected renaissance, Quechua folklore, texts, dances, and songs were preserved and shaped new literary and artistic manifestations, which have continued to this day. Playwrights in Cusco wrote Incan plays and rescued ancient texts, theater troupes traveled across the continent, and musicians preserved and performed Incan music. An official Misión Peruana de Arte Incaico under the leadership of Luis E. Valcárcel traveled to La Paz, Buenos Aires, and Montevideo in 1923 to promote Incan art and culture abroad as a way of making it, finally, become key to Peruvian national identity. The Compañía de Arte Incaico performed the much-applauded Quechua drama Ollantay with the actor Ochoa in the lead role in Buenos Aires’ famous Teatro Colón. We see below the Inka-inspired art deco poster of the event, as well as the photograph Chambi took of the theater company with director Luis Ochoa in Cusco in 1930.

Also making a lasting impact, Uriel García, Martín Chambi, and Manuel Figueroa Aznar founded El Instituto Americano de Arte in 1937 with the goal of creating new symbols of regional identity. Their vision was highly performative and symbolic. They designed the flag of Cusco, drawing inspiration from the flag of the Tawantinsuyu, or Inca Empire. It is still proudly placed next to the Peruvian flag in the Plaza de Armas and displayed during every major celebration. In 1934 Valcárcel led archeological digs uncovering the monolithic ruins at Sacsayhuamán that went on to become the stage for the first historical reconstruction of the Inti Raymi in 1944, directed by Faustino Espinoza Navarro and featuring indigenous actors. Held during the winter solstice on June 24, this celebration of the Inti or sun god, had been a religious ritual annually presented in Cusco’s main plaza since 1412, but it was banned by the Spaniards after their conquest in 1535. The indigenistas reconstructed the ritual from documents and oral tradition and also loosely based the reenactment on Inca Garcilaso’s writings. It has been held ever since and repeatedly reinvented and transformed. Today, thousands of school-age children as well as members from distant communities can be seen donning bright polyester ponchos and re-enacting the performance. A testament to the political and performative savvy of Cusco’s indigenistas, this celebration has not only fulfilled a vital role in the local community, but has also attracted millions of tourists. Chambi, of course, documented its various iterations.

Cusco’s indigenistas also affirmed the importance of indigenous epistemologies and cultural formations at the university, in the city, and in the country at large. They thus contributed to the convergence of the identity of the city with that of the Inca Empire, which resulted in what could be called a “neo-Inka revival.” With the “k” in the spelling of Inca, I mark the emergence of this new indigenous aesthetic and sensibility across Perú and other countries in Latin America. Indeed, the indigenistas fetishized the Incas, highlighting their grandeur and achievements at the expense of the former cultures that had long existed in the region: the Killke, Lucre, Marcavalle, and Wari, cultures that reached as far back as 3000 B.C., in fact making Cusco the longest continuously inhabited city in the Americas. Key to the transition from Inca to neo-Inka, then, was the failure of indigenistas to distinguish between the Inca period and the various cultures that came before and were absorbed into their empire. The indigenistas’s glorification and reification of the Inka resulted in their inability to fit Peru’s impoverished Indian communities into their narrative of cultural affirmation. In this, they inadvertently followed not only in the footsteps of Cusco’s elites who traced their genealogy to the vanquished Inca aristocracy, but also in those of archeologists intent on underlining the importance of the past, including Cusco’s ruins, at the expense of the present and the many forms of modernity that indigenous communities were adopting, and which Chambi and others were documenting.

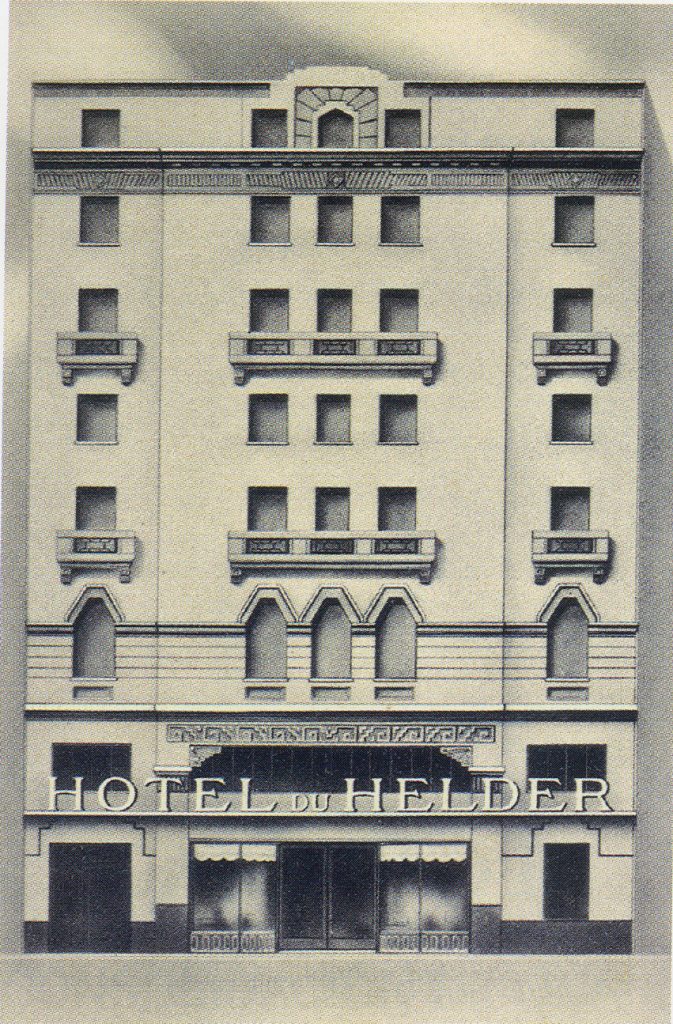

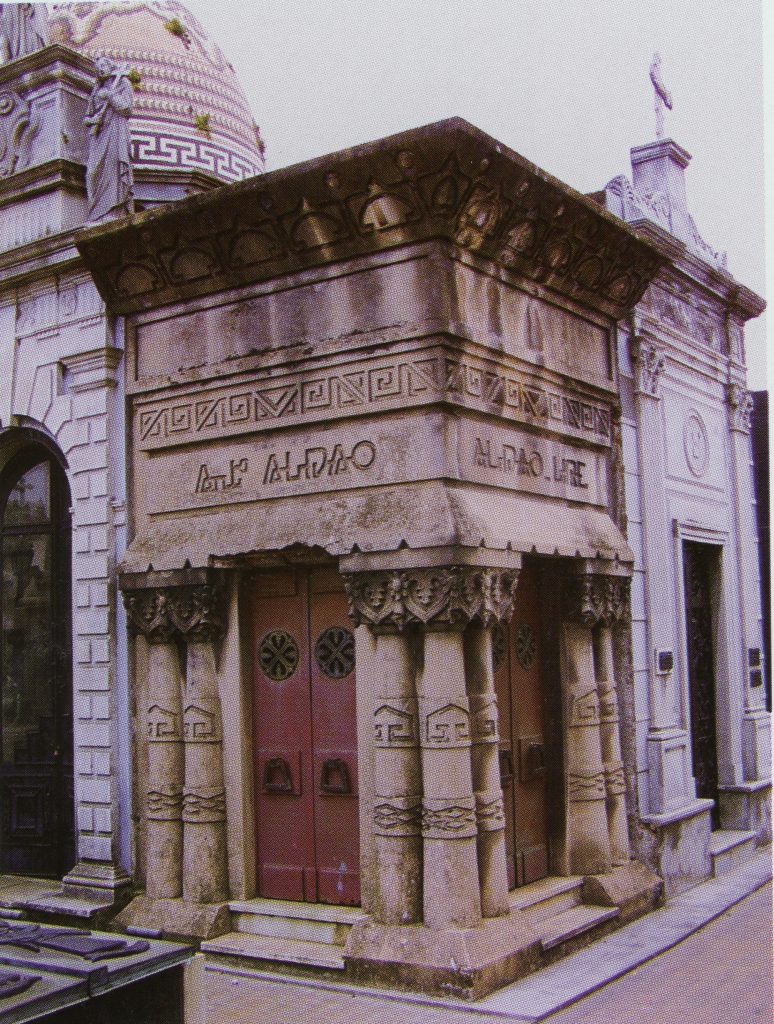

The dominance of the Inca period in the imaginary of the indigenistas, then, became a historical conceit and style in art and architecture, which already appeared at the Peruvian “indigenist” pavilion designed by Piqueras Cotolí for the 1929 Iberoamerican Fair in Seville. This “neo-Inka revival” was initially felt in the north of Argentina (Jujuy, Salta, and Tucumán) and then reached Buenos Aires. The discovery of Machu Picchu was much celebrated in newspapers and magazines in Buenos Aires, and Cusco-based photographers (Martin Chambi, Eulogio Nishiyama, et al.) and intellectuals (Valcárcel and others) were featured in Argentinean newspapers and magazines. They expounded the magnificence of Cusco and the city’s Inca ruins, which led to a veritable “Inca craze” in Buenos Aires and across Argentina. The University Reform of Tucumán was modeled on the one that had taken place in Cusco a decade earlier under Giesecke. The aesthetics of indigenismo were adopted and adapted in Argentina and inflected Art Deco with Inca motifs. In this, Latin American Art Deco after the “discovery” of Machu Picchu followed a very similar trajectory to that of the European movement’s incorporation of Egyptian motifs after the 1922 discovery of King Tutankhamen’s tomb. These neo-Inka styled motifs can be seen in many structures in Buenos Aires that were built in 1920s—a time when Sabogal and José Carlos Mariátegui were bemoaning Lima’s complete dismissal, even outright contempt for Andean culture.

Hotel du Helder, Angel y Alfredo Guido. House of Ricardo Rojas.1927. Courtesy of CEDODAL, Buenos Aires.

Aldao Mausoleum in Recoleta Cementary. Courtesy of Courtesy CEDODAL, Buenos Aires.

Teatro Colón, Compañía de arte incaico. Photo: Rodolfo Franco, 1923. Courtesy of CEDODAL, Buenos Aires.

Photos courtesy of CEDODAL, Buenos Aires

Although Argentina and Chile were European-focused countries that had largely decimated indigenous populations, the little-known Cusco-Buenos Aires connection potentially helps explain why they created their own sui generis form of performative indigenista nostalgia, manifested in folklore and music. From the early 20th century, various musical groups in Argentina and Chile adopted Andean musical instruments, melodies, and even dress (the iconic poncho). Most famously perhaps, Héctor Roberto Chavero, Argentina’s most important songwriter, took the stage name Atahualpa Yupanqui. Likewise, in Chile, which Chambi had also visited, the 1960s protest group Inti Illimani adopted the joint Quechua-Aymara name, and used Andean musical instruments and melodies to voice their protest against the Pinochet regime. Not exempt from exoticizing tendencies, in Peru too, in the 1950s Peruvian singer Zoila Augusta Emperatriz Chávarri del Castillo adopted the stage name Yma Sumac (which means very beautiful in Quechua) and toured the world. She would again re-exoticize the Inka and capitalize on this trend by claiming she was a “Virgin of the Sun” and descendant of Inca Atahualpa. In fact, she was born on the coast in the port city of Callao, next to Lima. Her dramatic performances of indigeneity became known worldwide. It is unclear how Antuca Vega Centeno at the Fototeca would have labeled a portrait of Yma Sumac.

The fluidity of identities that traverse even a traditional indigenous stronghold such as Cusco raises many questions regarding Andean archives both past and present: What happens to indigeneity in Cusco when indigeneity is adopted as a conceit not just in the city but also elsewhere in Latin America? What happens when a city in ruins is reconstructed in the interests of tourism and then preserved as a world heritage site—again, under the aegis of indigenismo, but also in the interests of tourism? Indeed, what happens to the status of ruins within contexts of repeated ruination and ongoing documentation of that process? Do we only see what has been lost and is irretrievable? Or do we see two things at once, as if each photograph were a double-exposure showing us what has been violently destroyed and simultaneously what has risen anew? Do we see the Inca in the neo-Inka and the loss and accretion that occur in the double image?

We found some answers to these questions during the month “El Cusco de Martín Chambi” was up in the streets. Indeed, the pristine black and white installations all over the city, as silent monoliths, seemed to interrupt—even break—the pattern of the crowded and colorful city familiar to all. With a sudden shock, passersby experienced them as a “double exposure” that instantaneously showed them two cities: the one it had been and the city today.