Reversing the Gaze. Photo: Silvia Spitta, 2012.

I came across this stencil/graffiti in Cusco a number of years ago as I was making my way to the famous photography archive at the Centro Bartolomé de las Casas—an NGO focused on outreach to indigenous comunidades. Inverting the visual hierarchy established by hordes of camera-wielding tourists in Cusco, it celebrates indigenous agency and photography’s role in creating a space for self-representation.

The woman holding the instamatic camera wears traditional clothes and also jeans and Adidas sneakers. She is returning the gaze and photographing a man with a red backpack, perhaps a tourist, perhaps one of the many researchers at the NGO. I wondered whether the graffiti’s proximity to the Fototeca might not have been altogether accidental; indeed, its placement might actually have been designed to interpellate them specifically. With a healthy dose of Andean humor, a little hummingbird is looking at her singing a famous huayno. A barely legible text reads: “Quisiera ser picaflor/para chuparte la miel/del capullo de tu boca” (I’d like to be a hummingbird/to suck the honey from your lips).

I happened upon it walking home after having spent the morning looking through some of the photographs held in one of Peru’s most important archives, the Fototeca Andina, which was the first archive I visited in Cusco. It is housed at the Centro Bartolomé de las Casas, named in honor of the Spanish Bishop of Chiapas; he was one of the first to deplore the atrocities committed by the colonizers against indigenous peoples and was officially appointed as “Protector of the Indians.” Founded by European anthropologists in 1988, the NGO focuses on education and communications social programs. There is a Casa Campesina where members from remote campesino communities looking for medical or legal services in the city can stay for a small fee. It has a well-regarded publishing house that disseminates scholarly work done at the NGO and in the Andes. It also houses the world famous photography archive, the Fototeca Andina—founded by Deborah Poole and Adelma Benavente—which currently holds around 35,000 glass plate photographs taken by 45 photographers in the southern Peruvian Andes between 1850 and 1960.

The gaze is gentler, the viewpoint much more familiar. The camera brings Andean inhabitants closer, and in doing this, the photographs open up a world to which Western photographers were not privy.

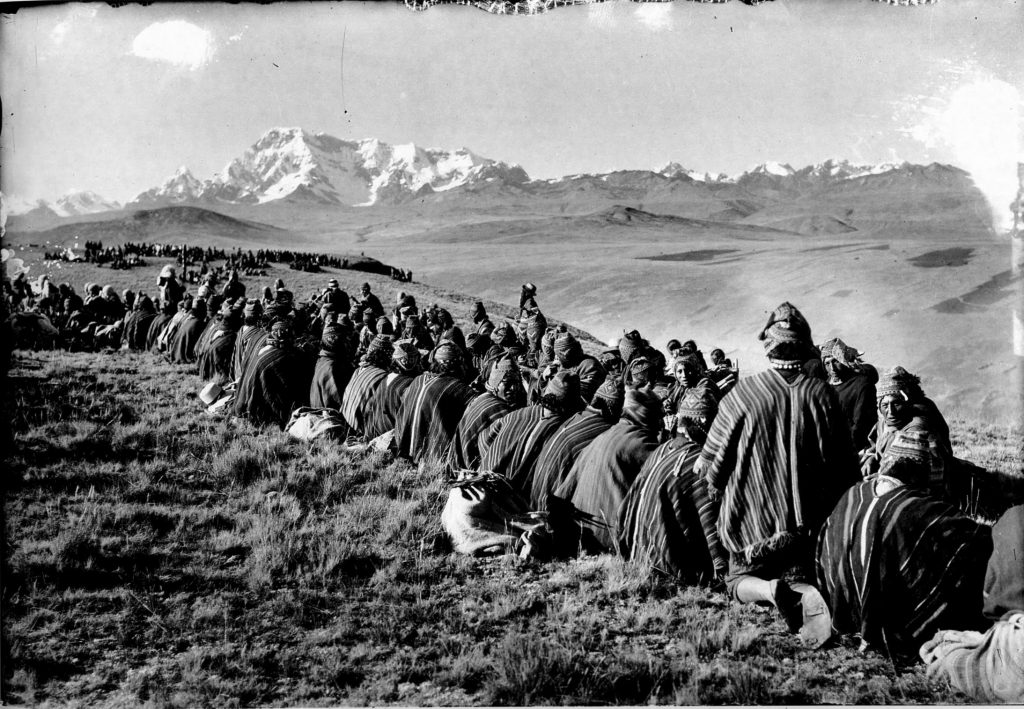

Unwittingly, the turning of the gaze inscribed by the stencil/graffiti represents the reason why the holdings at the Fototeca are so important and considered an invaluable patrimony and archive of alterity. That is, it counters the imperial visual field and violence produced by Western photography when it was wielded by engineers, archeologists, and other scientists who arrived in the Andes in the late 19th century. The sale of smaller Kodak cameras in 1888, however, allowed the medium to be democratized and appropriated; photography quickly also became inseparable from the representation and celebration of middle- and upper-class family life. This is true of many of the photographs in the archive at the Fototeca, which feature a large majority of Cusco’s elites who could afford to be photographed in the city’s studios. But what makes this archive so special is that many of the photographers were local, and some were indigenous, and they photographed many other aspects of their world as well. Together, and viewed as a collection, the photographs provide as complete a record as any of all aspects of life in the southern Peruvian Andes during a period of modernization and profound transformation as electricity, cars, airplanes, and with them archeologists, immigrants, and mass tourism arrived in the city.

Unlike much of Western photography, which tends either to inscribe coloniality and the power differential that existed between the photographer and his subjects or underline the subject’s poverty or difference, the photographs in the archive achieve a more horizontal point of view. The gaze is gentler, the viewpoint much more familiar. The camera brings Andean inhabitants closer, and in doing this, the photographs open up a world to which Western photographers were not privy. Beyond traditional forms of social and studio photography (centering around typical family events such as engagements, weddings, burials, and religious celebrations), the photographs also highlight the impact of modernization and the fascination with extraordinary events of the time. These include the inauguration of the first rail line and arrivals of the first car, motorcycle, and plane to Cusco. Other photographs document Titanic-like failures that stemmed from the belief in the invincibility of modern inventions such as that of a truck trying to cross a hanging bridge—with obvious results. Staged photographs, in true Andean comic fashion, also play with these symbols of modernization by showing scenes of simulated car crashes or onlookers gawking at a train derailment as if at a carnival. Stunning images also capture the devastating earthquake that destroyed much of Cusco in 1950 as it was happening, and they served as a guide that assisted architects as they rebuilt the city.

The Fototeca, known worldwide for its holdings, is open to researchers and visitors. However, undermining this openness, the legal status of many of the archive’s holdings is uncertain, thereby limiting what can be done with the materials, including publishing. Many families donated photographs but did not release the copyright; many, like the Nishiyamas, are engaged in futile legal battles. Moreover, the staff at the Fototeca is typically trained in communications and campesino outreach—not in archival preservation or photography—but as often happens in archives everywhere, they tend to see the archive as a “treasure” that needs to be protected at all costs. Trying to work with the archive, the researcher instead feels as if one impediment after another is being raised. This kind of misplaced protectiveness, I realized, runs counter to an archive’s raison d’être. That is, archives are there as an important repository for scholars, yes, but they also need to serve the common good and preserve the past to illuminate the present. The term “archive fever” was created by Derrida to point out that the creative, accumulative activity of archives is always, inevitably, threatened by the forces of destruction. One such force, of course, is protectiveness when it becomes an end in and of itself; the archive may be safe, but it is unable to serve as a public commons. My incursion into the Fototeca, which I will describe further in what follows, taught me this and also that archives run the danger of becoming mere storage spaces if they are not put in dialogue with the community where they are housed—especially, as in the case of Cusco—where they arose.

As I worked for weeks on end at the Fototeca Andina, I was repeatedly humbled as I looked at hundreds of photographs of ruins, deceased people, families I never knew and would never meet, and photographs of events in the life of a city to which I had not been privy and thus had no way of situating or reconstructing. Indeed, many scholars repeatedly fail to come to terms with this new visual discourse and tend to supplement their frustration at the archive’s indecipherability with epistemological schemes that reduce its alterity. In study after study, indigenous people emerge either silenced or associated, as we will see in the next sections, with ruins and the past—in other words, as dead culture. Like many before me, I too felt epistemologically adrift and existentially alone amid what began to feel like a massive intrusion of the past into my life. Repeatedly reminded of Barthes’ association of photography with death, I attempted to hold the ghosts inhabiting the archive at bay by making aesthetic judgments about the photographs, or simply by being overcome by sheer awe at the mastery of the photographers and the beauty of the images. Yet, beyond these oddly reductive judgments that circumscribed the archive to the aesthetic realm, the archive remained silent and indecipherable. I realized that it was hard to glean much information from the images themselves. I left the archive on many days with the uncanny feeling that I had been spending my day among ghosts.

Instrumental in founding the Fototeca Andina, Deborah Poole has also written one of the first books on the Cusco School of photography: Vision, Race, and Modernity: A Visual Economy of the Andean Image World (1997). In her extended study she traces the development, transformation, and uses of photography in the Andes since its arrival. This outstanding historical and semiotic analysis of the ways in which photography registered modernity in Cusco, however, ends with a sobering reflection on the limits of photography, and on a photograph’s inability to tell a story once that story has been lost. Poole paradoxically concludes by voicing her uncertainty regarding her inability to answer the very questions about identity and modernity that had driven her study. “As an anthropologist,” she writes, “I am skeptical about my ability to answer these questions concerning Cusqueños’ modernities, selves, resistances, and identities by simply looking at pictures.” More tellingly, she continues, “Even after my excursion into the historical archive, I retain a residual unease about speaking for these mute Andean subjects” (213, emphasis mine).

Anthropologist Antuca Vega Centeno, working at the Fototeca over many years, inadvertently overcame Poole’s limitation when she devised various strategies for obtaining information about the images and getting them to “speak.” A volunteer at the archive, she was able to approximate the dates of all the photographs, combining her training as an anthropologist, her insider’s knowledge as a member of Cusco’s elite, as well as her interest in the history of fashion. She proved key in “enlivening” the images for me in sometimes surprising ways. Since she was quite elderly, she had known some of the people in the photographs and could place the images within personal, cultural, and historical contexts that I would never have otherwise known. Sometimes, she told me, she surreptitiously took photographs home to show her friends in search of information about the subjects in the photographs. I vividly remember one anecdote she told me of a photograph she found of a friend in her circle who had posed in a studio almost naked. When she took the photograph out of the archive to show her, her friend vehemently denied it was her.

She also classified many of the photographs with a term that repeatedly baffled me: “disfrazados” (disguised). She attached this label almost invariably to photographs of Cusqueños wearing indigenous clothes. Her category was clear to me when the photographs were of people at a carnival or theatrical representation, but at other times, it was totally unclear. I came to realize that in her experience, Cusqueños wore Western clothing. Simply put—they were modern. Indigenous clothing was donned to celebrate and/or mark special occasions. Indeed, their use constituted a strategic performance of indigeneity and of claiming Inca lineage that had roots in the colonial era; whereas elites had to prove their Inca nobility to avoid taxes levied on the lower castes. Given the establishment of this colonial caste, it is not surprising that in the early 20th century, it became fashionable among Cusco’s elites and even among Italian, Spanish, German, and English immigrants to dress up in this style and pose in Chambi’s studio. Antuca Vega Centeno’s label “disfrazados” references this past tradition and points to the performative indigeneity that was emerging in her time.

That is, we need to establish paths and possibilities for a dialogue across time between the archive and the community where it “lives.”

Antuca’s invaluable help, and her breaking the Fototeca’s rules to take photographs out of the archive, convinced me more than ever of the importance and urgency of involving the community in the re-construction of a photograph’s “metadata.” That is, we need to establish paths and possibilities for a dialogue across time between the archive and the community where it “lives.” We need to reconstruct important events, record stories, and in the case of Cusco’s archives, attach a story, a time, and a context to the images before that history and memory are irretrievably lost. Given the fact that many of Cusco’s archives hold images of people who might have not yet passed or who could be recognized by their descendants, I realized that they need to be “enlivened” so that they are not reduced to spaces inhabited by ghosts and mute subjects. Archives truly only live up to their full potential when they are allowed to come alive in the present.

“Living Archives” projects around the world have countered the tendency of archives to become zealously overprotective and therefore closed off from the communities where they arose and are housed. Various creative strategies for taking archives out into the streets have been devised. In Uruguay, the Centro de Fotografía, established in 2002 under the brilliant directorship of Daniel Sosa, created 3 exhibition spaces on site, but also free, open air photo galleries across the city (in the central Parque Rodó, as well as in Ciudad Vieja, Villa Dolores, and Peñarol). The visitor thus accidentally encounters numerous exhibitions and leaves Montevideo with the memory of having been in a city of images. Indeed, the Centro de Fotografía’s mission is to mobilize the historical images of Montevideo in its holdings, as well as those that document the present, in order to create a sense of citizenship and belonging in the city “a partir de la promoción de una iconósfera cercana” (“by creating an intimate iconosphere”)(http://cdf.montevideo.gub.uy/content/quienes-somos). The archive thus aims to intervene strategically into a landscape already saturated with images. It also attempts to foster a critical stance towards images and aid citizens in producing their own image world out of this encounter.

Another example of a successful intervention into the archive is that of Susan Meiselas, who returned to Nicaragua ten years after she had documented the Sandinista revolution. The book Nicaragua, June 1978 to July 1979 (1981) is an account of this intervention and the documentary Pictures of a Revolution (1992) records her experiences searching for and talking to some of the subjects of her photographs. In 2004, 25 years later, she once again returned to exhibit some of the photographs she had taken there in the late 70s at the height of the Sandinista revolution when, as a young photographer, she was caught in the midst of the conflict. Reframing History was a city-wide event in which she staged the enlarged photographs of the conflict as huge semi-transparent billboards in the very spaces where she had taken them years before, and which surreally blended with the present. During the exhibit she interviewed people to see what they remembered about the revolution. Part of that work was exhibited at the Institute of Contemporary Photography (ICP)in New York. The twelve minute video “Reframing History” (2004) records the encounter and the memory and re-framing effect of the images. Susan Meiselas’ continued interventions into her own archive shed light on an important period in the life of the country, on the nature and “work” of photography, the all-too present danger of forgetting, and the imperative to create an archive of the archive. A living archive.

Likewise, Vera Lentz photographed the internal conflict between Peruvian government forces and the Maoist Shining Path movement that ravaged the country for two decades (1980-2000), leaving over 70,000 dead. Inspired by Meiselas, she returned to Ayacucho in the early 2000s to show the victims of the violence the photographs that she had taken there when few Limeños dared to venture outside of Lima. Her return was first documented in the 2004 documentary State of Fear (Dir. Pamela Yates) and now more recently in Volver a Ver (Dir. Judith Vélez, 2019). Meiselas’ and Lentz’s works have to be situated within a long tradition in Latin America where photography has inhabited a complex field permeated by performance and politics. This was most evident in Argentina, where the Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo famously marched around the Plaza every Thursday holding up photographs of their disappeared children. This performance gained them worldwide attention and helped delegitimate the Junta. More recently, Ni Una Más, the nation-wide movement in Mexico which started out protesting femicide on the US-Mexico border, particularly Ciudad Juárez, uses photographs of the femicides and the disappeared to denounce narco terror and the state’s necropolitics. In Argentina, the Ni Una Menos movement mobilizes photographs of victims and performance strategies to protest gender-based violence and has now spread across the continent.

Inspired by these multiple, often highly performative deployments of photography, I turned to Cusco’s archives since they register the life of a once traditional Andean city and region undergoing vertiginous modernization. The region benefited from improved communications by car, rail, and plane, and became traversed by global networks of influence and power. Within the saturated image world that resulted out of the confluence of modernization and the legacy of colonialism, Martín Chambi’s archive is unsurpassed as an invaluable artistic testament of that period of transition and as an important motor in the representation of a modern sensibility in the city. Indeed, Chambi’s personal—even intimate—knowledge of Cusco serves as an important corrective to Western anthropology’s photographic construction of indigenous Andean culture as either backward, frozen in stone, bypassed by modernity and thus yet another form of “ruin,” or simply “inscrutable.”