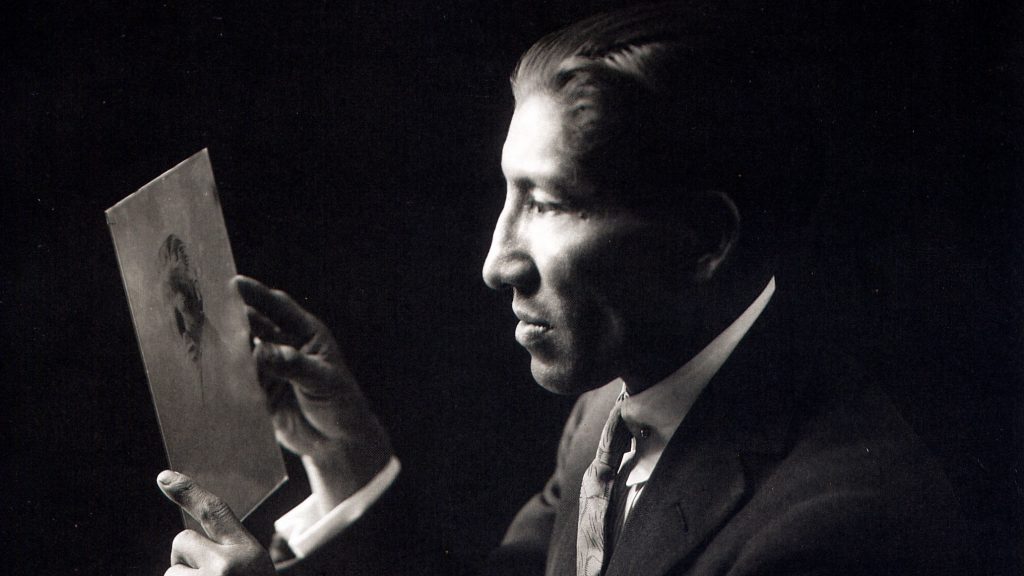

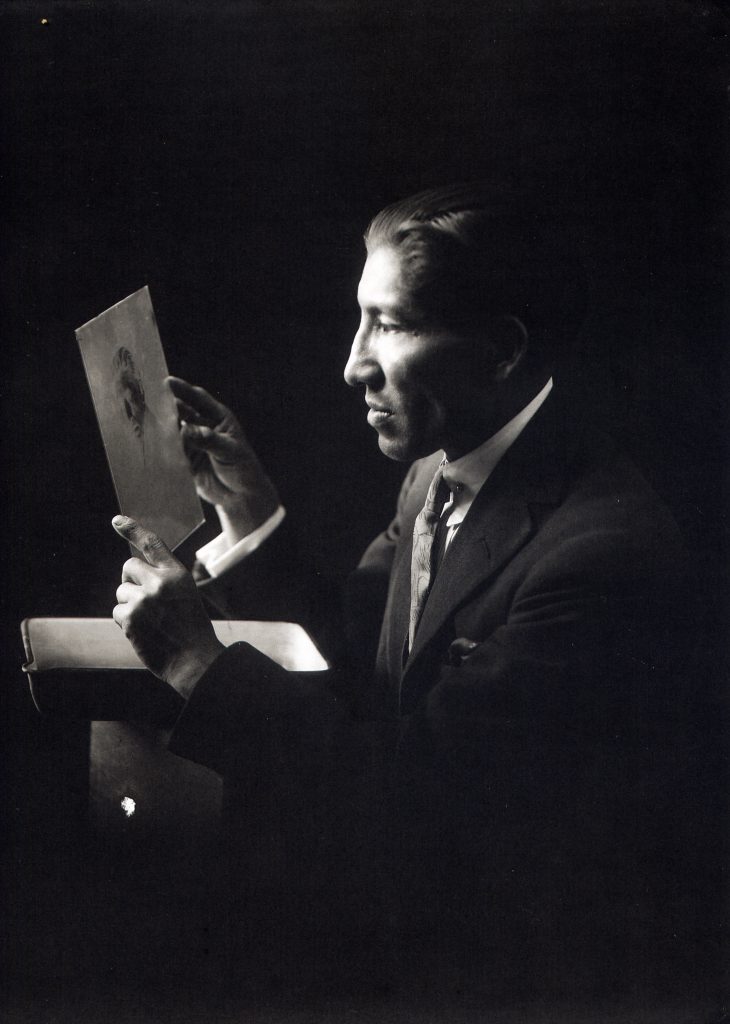

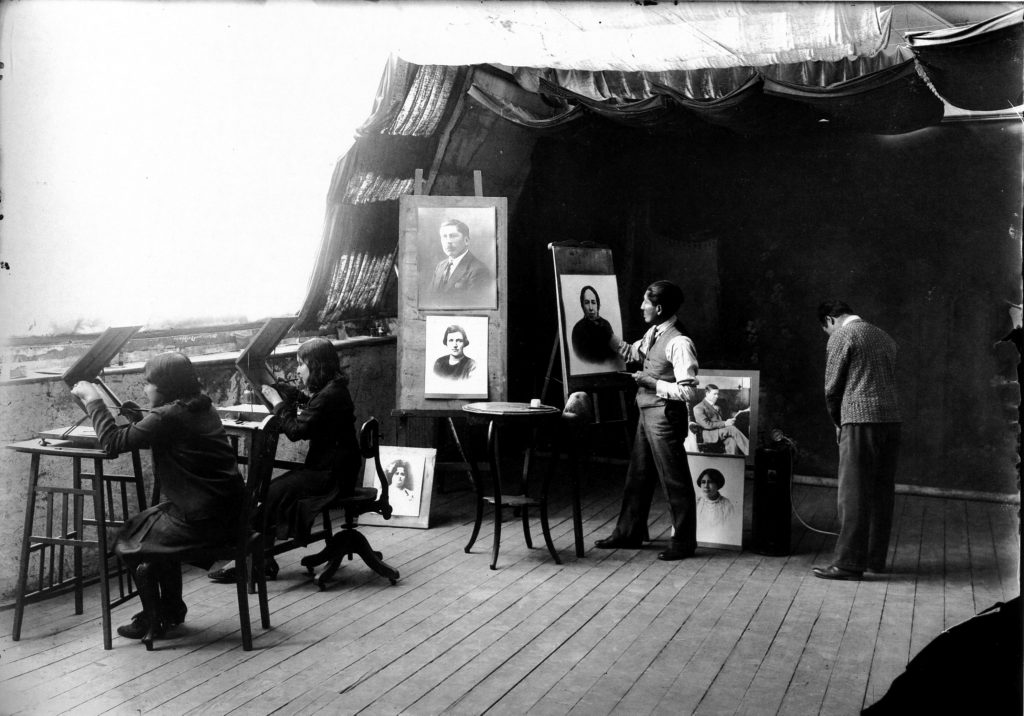

Since Daguerre (1787-1851) first fixed images on highly polished, light sensitive silver-plated copper sheets, photography’s reach has expanded exponentially. As today’s selfie fever attests, photography has become intrinsic to, and inseparable from, the performance of identity. Both a tool in representation and a creator of the need to be represented, in less than two hundred years, photography has erected itself between the subject and the object, the self and the other. Long before the selfie, the above carefully staged self-portrait of indigenous photographer Martín Chambi shows him holding up a glass plate negative of another self-portrait he most likely had taken. It is a prescient staging of the future role of photographs in our lives and anticipates efforts by native peoples worldwide, which are increasingly gathering momentum, to wrest photography away from imperial visual regimes. While much has been made of the relation between photography and death—in particular, the notion that a photograph represents a moment that is always already in the past—this stunning self-portrait really does seem almost as if Chambi were looking at himself as a ghost. The self-portrait also plays with the intrinsic reproducibility and itinerancy of photographs, not only from glass plate to print as we see here, but also across cultures, times, and the meanings attached to images. It also brilliantly stages a particularly Andean need of, and agency in, self-representation.

The image arrests the eye and draws attention to the divide between the great photographer and the glass plate negative photograph that we presume is an earlier self-portrait. Chambi’s face and the glass plate come out of the shadows, illuminated by the light shining through the skylight of his famous studio in Cusco on Calle Marquez. While in most of the many self-portraits that he took throughout his life, an invisible assistant in the studio snapped the shutter; in this case, his grandson Teo told me, Chambi held a cable connected to the camera that allowed him to take the shot. This selfie avant la lettre, then, is a stunning celebration of an indigenous photographer’s appropriation of a Western medium to represent himself, and through him, his community. Given how other-directed and other-inflected it is, this image is both a homage to Rembrandt and a staging of the photographer as a photographic subject. As his figure comes out of the shadows thanks to the light streaming in through the window, Chambi seems to be underlining his dark skin color, his indigeneity, as well as his position as a respected professional in the city—and thus his modernity. The carefully crafted self-portrait, with its sheer power, lays bare the insidious ways in which Western photography’s construction of alterity would shape, and fundamentally distort, our visual field.

Chambi’s great gesture and achievement, then, was to take a European lens, handmaiden of empire, and turn it onto his world, poignantly photographing it from within with all its gradations and nuances.

Glass plate photography was so valued at the time because it allowed for a difficult-to-match degree of resolution, but also because the glass plates could be touched up in the studio to whiten people or to delete blemishes. We therefore have here, in 1923, in the Andes, a foreshadowing not only of photoshop, but also of the role photography has come to occupy in our lives. Given the importance of a studio’s capacity to manipulate the images in response to people’s deepest desires, it is telling that in the many self-portraits Chambi took throughout his life, he never whitened himself or otherwise touched up his self-portraits.

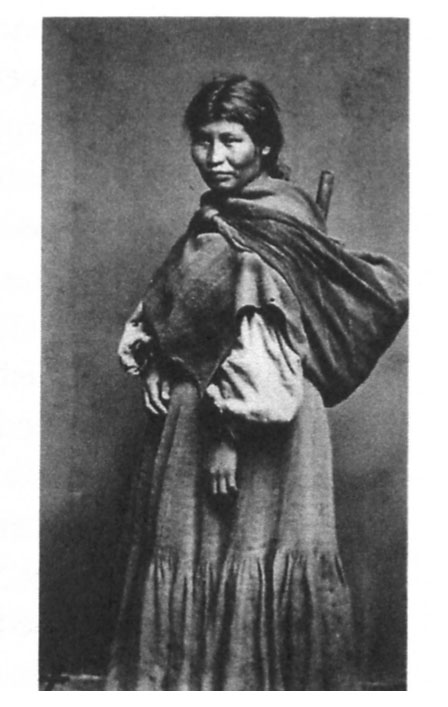

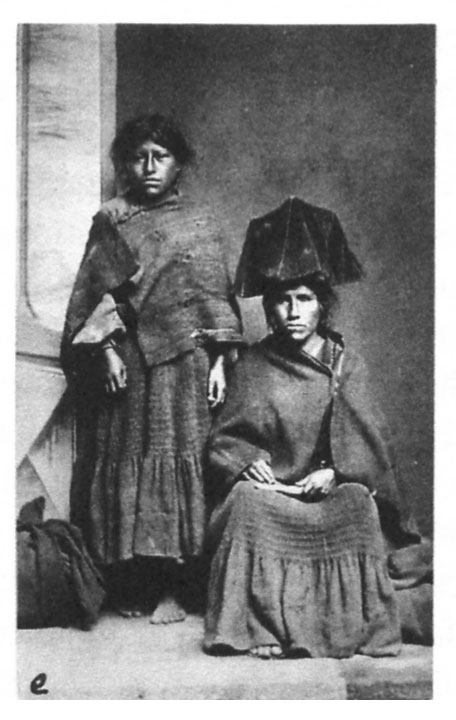

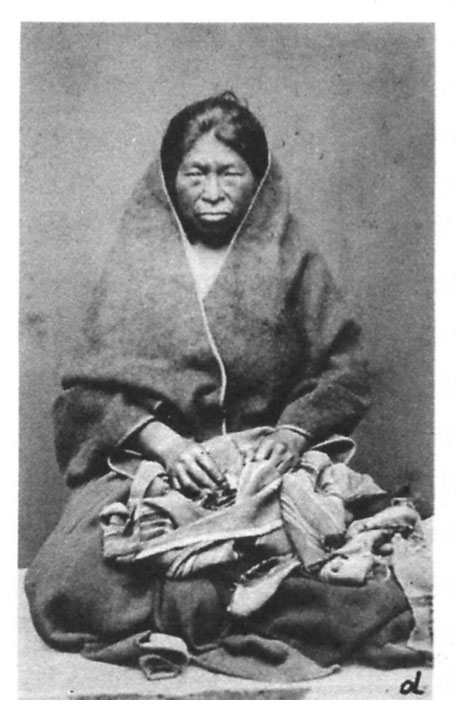

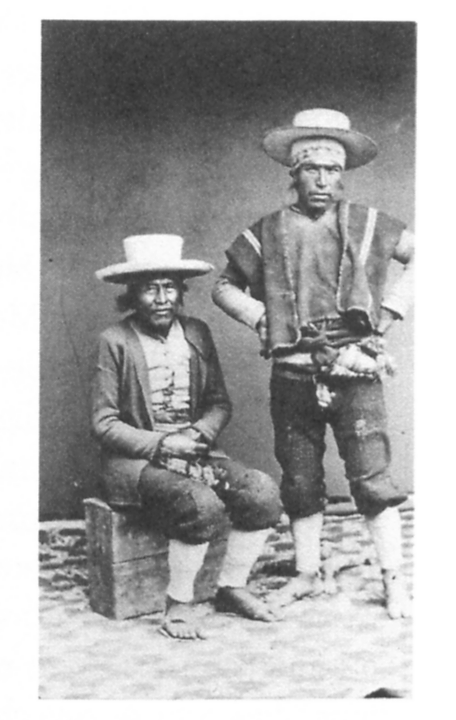

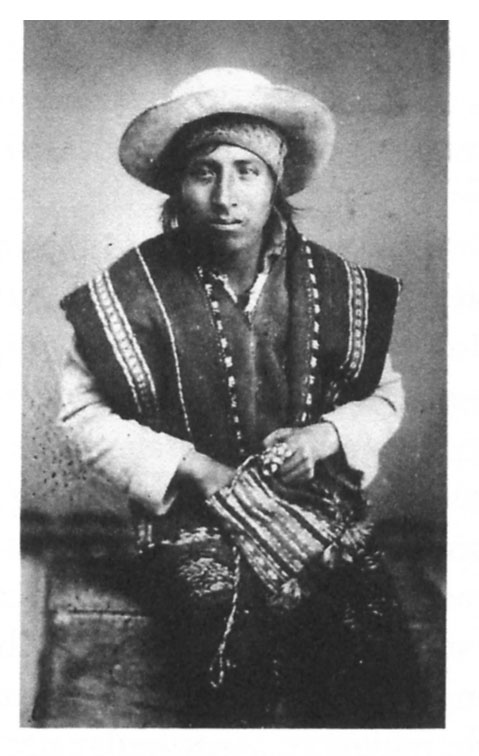

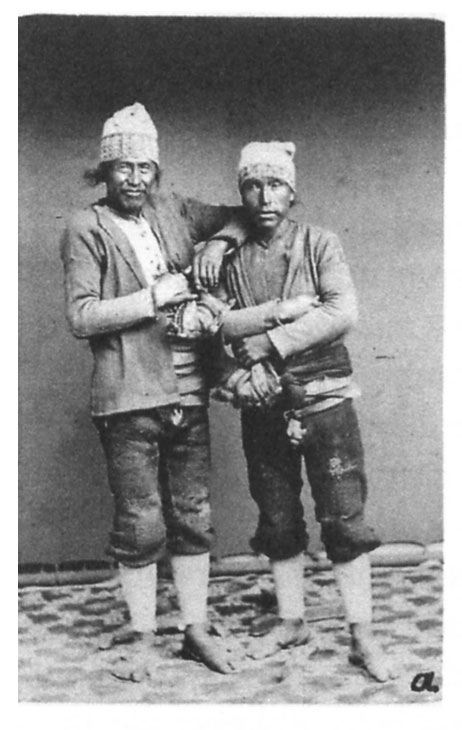

Chambi’s great gesture and achievement, then, was to take a European lens, handmaiden of empire, and turn it onto his world, poignantly photographing it from within with all its gradations and nuances. His self-presentation and self-representation counters a long Western tradition of framing native photographic subjects as non-modern and therefore outside history, bypassed by modernity, and most often as mere abject “types.” In Peru, early photographs used in cartes de visite—forerunners of modern “calling cards”—often highlighted the poverty of indigenous people, who were to be viewed as curiosities or framed in other similarly abject ways. The look of hatred and resentment in the eyes of many of these subjects is testimony to the many demeaning forms of subjection they suffered, which included, in this case, the violence inflicted on them by the photographer as he made them pose.

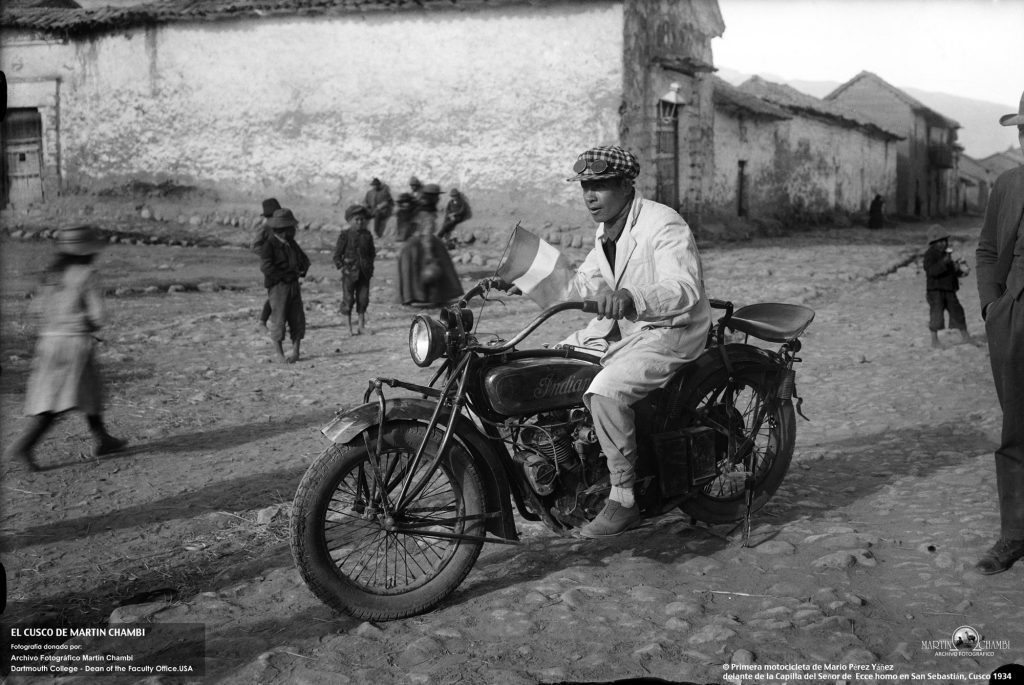

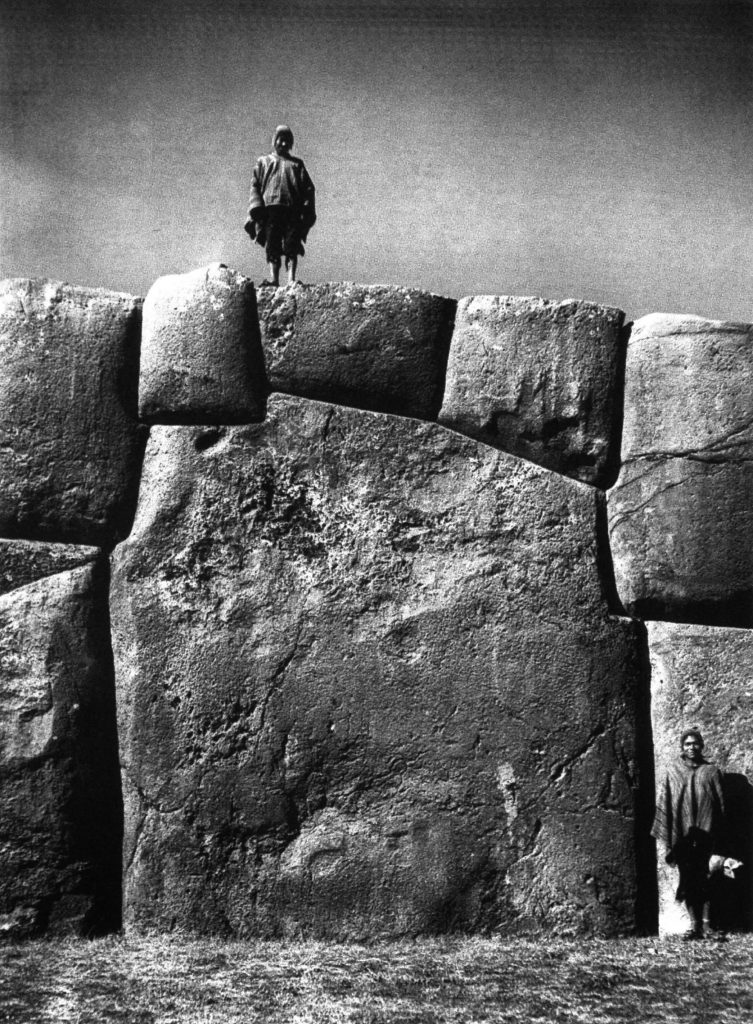

These cartes de visite circulated worldwide, helping to create negative stereotypes of indigenous people that have persisted to this day. Postcards celebrating the great archeological discoveries of the time also circled the globe and further buttressed these notions. Photographs celebrating ruins thus served to reinforce the association of photography with death and the past—and in the case of Cusco, conflate its ruins and its people. The region’s vast and imposing archeological ruins became inextricably associated with indigenous people, seen as mere vestiges of the past, left behind by modernity. Chambi would, of course, counter these damaging notions. Indeed, throughout his life he insisted on showing Cusqueños’ transformation and modernization. That is, he portrayed a modern indigeneity.

This famous 1934 photograph of his friend Mario Pérez Yáñez riding the first motorcycle in Cusco in white overalls to protect his suit from the dust is typically read as a celebration of the arrival of modernity in the Andes. It is a clear example of Chambi’s linking indigeneity and modernity. Moreover, the Peruvian flag attached to the handlebars, situated almost at the exact center of the image, eloquently center stages his demand to be included as modern in the national narrative.

Chambi’s great achievement, then, was to document daily life with all its intricacies in a once-traditional city undergoing rapid modernization. He photographed the largely Incan-descended elites as well as European and Asian immigrants to the city in his studio, and he used the money he earned there to buy the expensive glass plates and go out into the streets. He frequented the markets and befriended the chicheras; he photographed beggars, children, campesinos during market day, and many other scenes of daily life. He also traveled far and wide around the southern Peruvian Andes. Unlike many studio photographers, Chambi had no interest in staying exclusively in his studio and photographing one class of people his entire life. He did not avoid or deflect his gaze from thorny social problems, and he excelled at staging the myriad ways colonialism taught us to disavow the profound oppression of indigenous communities. He teaches us to look and to see other-wise. Two photographs in particular illustrate how he made us aware of the colonizing gaze with its limitations and distortions.

In this photograph of Hatun Rumiyoc street, taken at the entry to what is today the Museo Arzobispal, the eye is drawn along the massive Incan walls down the street to the vanishing point in the sun. We notice only gradually that two campesinos in their ponchos are standing by the door of the museum. Once we see them, we begin to look down the street at the vanishing point and then at them, back and forth. The oscillation between two viewpoints at play in this photograph feels destabilizing and reminds us of Walter Benjamin’s dictum that this type of deflection is the “optical unconscious” of our time. Aware of this, Chambi stages his photographs to show us how Western photography has trained us to either see what we see and how we see or—perhaps even worse—not to see.

Likewise, in one of Chambi’s most celebrated images, “Novia en mansión Montes, 1930,” we look in admiration at the bride in her regal bridal dress draping over an equally regal stairway that we imagine is lush red. While her proud stance and the imposing stairs draw our attention into the frame, we slowly and belatedly notice a figure to the right of the stairway; we begin to see an Indian servant emerging from the shadows, and we realize—eerily and with a momentary shock—that she has been looking at us all along. As he does in his “self-portrait,” where he is performatively insisting on his dual role as a professional and as an indigenous photographer, in “Novia en mansión Montes” he plays with our gaze by making us see two things at once. The whiteness of the bridal train and the darkness enveloping the servant could not be a more eloquent testimony of the racial and class division operant in Cusco at the time. Chambi’s photograph teaches us to see by rending the veil from what we typically do not see.

Unlike many studio photographers, Chambi had no interest in staying exclusively in his studio and photographing one class of people his entire life. He did not avoid or deflect his gaze from thorny social problems, and he excelled at staging the myriad ways colonialism taught us to disavow the profound oppression of indigenous communities. He teaches us to look and to see other-wise.

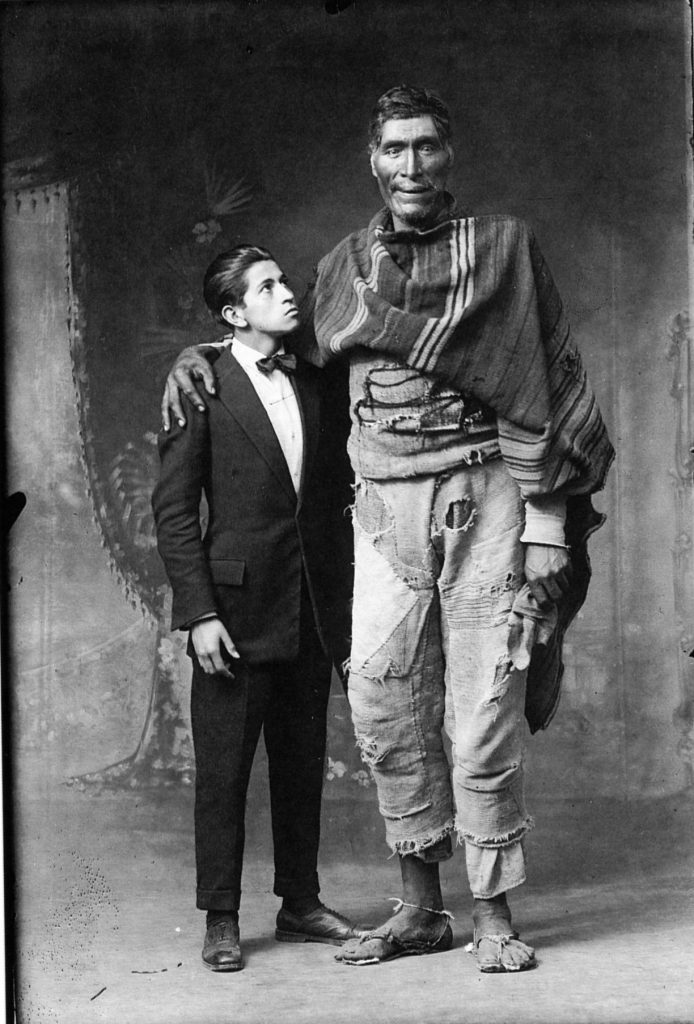

In stark contrast to the colonial tradition of othering, objectifying, or demeaning the photographed subjects, Chambi’s portraits give us an intimate glimpse into his city and his world. Critics Jorge Villacorta and Andrés Garay point out that he saw and photographed a millenary culture with modern eyes and instruments. They celebrate his exquisite and dramatic photographs of Machu Picchu, as well as his ability to manipulate light. Dramatic chiaroscuros have made Chambi known as the “poet of light” (poeta de la luz) and led to comparisons with European masters like Rembrandt. But most of all, he is recognized for his uncanny ability to make his photographic subjects—from the most privileged to the most humble—feel fully at ease before the camera. His is a “loving” gaze (una mirada que acaricia), one that allows his subjects to emerge from his photographs as dignified, self-possessed subjects, regardless of the oftentimes terrible circumstances in which they find themselves. The portrait he took in his studio of the so-called “giant of Paruro,” chosen for the cover of Martin Chambi, 1920-1950, is only one example, among a myriad others, of the gentleness and unguarded look he was able to elicit in the eyes of his subjects. If we go back to look at the eyes of the subjects in the cartes de visite, we see hurt, resistance, and hatred. The contrast between them could not be more telling of the violence to which photography can subject people viewed and framed as inferior.

Famous portraits such as this one of two giants, one literal and one virtual, of fellow artist Mendívil and a cargador in Cusco, mark the distance between the subjects of Chambi’s photographs and the resistance, and even outright hostility, with which subjects who are framed by an anthropological lens look back at us across time. Unlike the creators of these degrading images, Chambi aspired to encompass the entire gamut of life in the Andes. Whereas indigenous people had been relegated to an archaic past, Chambi photographed everyday life in the streets and markets of the city and environs as well as the city’s elites. The above photograph conjoins both. The images taken in his studio, as well as those shot in various locations across the Andes, then, are stunning for the profound glimpse they allow us into a long-misrepresented culture.

A Quechua native, Chambi grew up in an indigenous community in very humble circumstances. He was born in 1891 in the village of Coaza, in the vicinity of Lake Titicaca, at over 4,000 meters above sea level. As an adolescent, he learned photography from the English engineers who arrived in the vicinity of his village alongside the gold mine that destroyed his family’s livelihood. Inspired to become a photographer, he moved to Arequipa when he was 17 and became an apprentice in the famous studios of Max T. Vargas as well as that of the Vargas brothers at the Portal de Flores on Plaza de Armas. Once he felt that he had perfected his skills, he ended his stay in Arequipa with an exhibit of his works in the Artistic Center of that city on October 12, 1917. He married Manuela López Visa from Arequipa’s elite, and together with their first children they moved to Sicuani. In 1920, he settled in Cusco with his growing family. As an immigrant from the remote highlands of Puno, he was looked down upon in Cusco, the former center of Inca and pre-Inca power. Yet, he proudly adopted the city as his own and worked throughout his life to preserve its cultural heritage and promote its wonders throughout the world. Eventually, in the very space that had once been occupied by another great photographer, Juan Manuel Figueroa Aznar, he opened the studio that would make him renowned worldwide.

Perhaps because he was not originally from Cusco, Chambi saw the city with the admiration and love that foreigners bring with them. He was key in creating some of the iconic images that would make Cusco a world heritage site and tourist destination long before the downside of tourism would come into focus. An example is his famous photograph “Indian and Llama,” which he sold as a postcard. This stylized backlit silhouette of an Indian with a llama on the crest of a mountain is a timeless image that has circled the globe and only recently, with Chambi’s rising fame, was finally attributed to him. While it participates in the indigenista movement’s stylization of indigeneity that I will discuss at greater length below, the other names under which the image is known, “La soledad del indio” or “Tristeza andina,” show that it is a profoundly moving portrait of the transcendental solitude and political and economic marginalization of indigenous people in Peru while also being an image designed to be legible to a global audience.

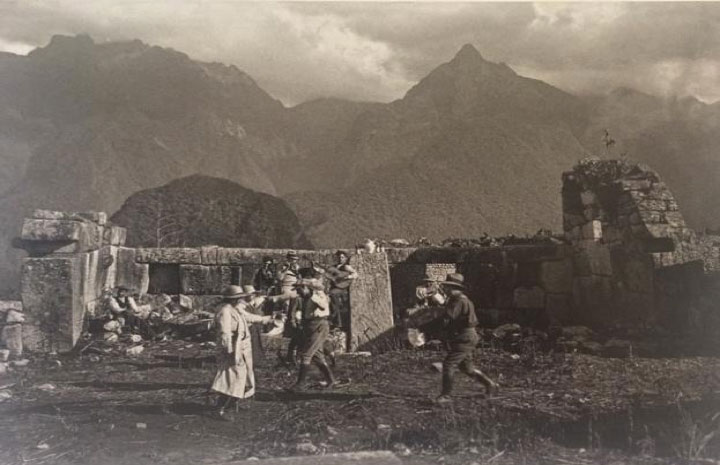

While Chambi created some of the most moving and intimate portraits of native life, he too, like the archeologists working in Cusco, quickly understood the value of Cusco’s ruins in buttressing the status of indigenous Andeans, not only in Lima but also worldwide. In this, Machu Picchu, after the savvy marketing of Hiram Bingham’s “discovery” that quickly made it a tourist destination and soon a UNESCO world heritage site, was key. The promotion of this site would change the region irretrievably, and Chambi, who photographed it repeatedly over the years along with many other photographers such as Manuel Figueroa Aznar, Max T. Vargas, and Eulogio Nishiyama, wanted the world to admire the great achievements of his culture. He joined in the celebration of the discovery and also documented the gradual emergence of the ruins as the site was cleared of the jungle that had encroached upon it. It is now known that Hiram Bingham heard of Machu Picchu from local campesinos who lived in the vicinity and still farmed the famed terraces of the site. The site, then, had never been abandoned. It was a living ruin. In contrast to Bingham and other archeologists who claimed the special status of Machu Picchu and fetishized it as a monument of the past and to the past, Chambi instead saw it as a living space continuous with the present. The magnificent photograph “Excursión de Ricarda Luna y amigos” below shows the group joyously dancing in the ruins at Machu Picchu. The photograph not only documents the visit of Ricarda Luna, one of Cusco’s renowned socialites and philanthropists, it also shows the celebratory spirit of the moment. As they dance, Ricarda Luna and his friends are “enlivening” the ruins and affirming the continuity and transformation of Andean culture. That moment, more than anything else, displays how Cusqueños refused foreign archeologists’ fetishization of Cusco’s ruins as dead. Indeed, every time groups such as this inhabited the space, they were performing the ruins and re-inscribing them with their sheer presence.

As Walter Benjamin pithily expressed in 1928: “Allegories are, in the realm of thoughts, what ruins are in the realm of things.” While archeologists insisted on unearthing a monumental past culture, Chambi saw the ruins as very much alive and a part of the present. This difference between two ways of seeing ruins, and by extension, Andean culture, best explains why critics celebrate and emphasize Chambi’s indigeneity. Horacio Ochoa’s 1940 photograph “Campesinos en Sacsahuamán” makes this distinction even clearer. We see that the archeologist who most likely asked Ochoa to take the photograph has positioned one campesino next to the monolith and the other on top of it, using them as a measure of its sheer size and the unmatched technical ability that went into its making. Creating a jarring contrast between past and present, the campesinos standing there in their humble ponchos do not—indeed, cannot—measure up.

That same year, Chambi would take a similar, yet very different, photograph. As we see below, “Nestor Rafael Guerra en el Qoricancha, 1940” shows a man dressed in a formal suit and tie and wearing a hat, lying at the base of the famous reconstructed “drum” stone wall of the temple to the sun, which had been destroyed during the conquest. Unlike the impoverished campesinos in Ochoa’s photograph, whom modernity has bypassed, Guerra, in his formal, Western attire is positioned as modern and cosmopolitan. Although the earthen floor might not have been that comfortable, he looks as if he were at a Sunday outing. He is clearly upper class and most likely imitating the English dandies that arrived in Cusco during that period.

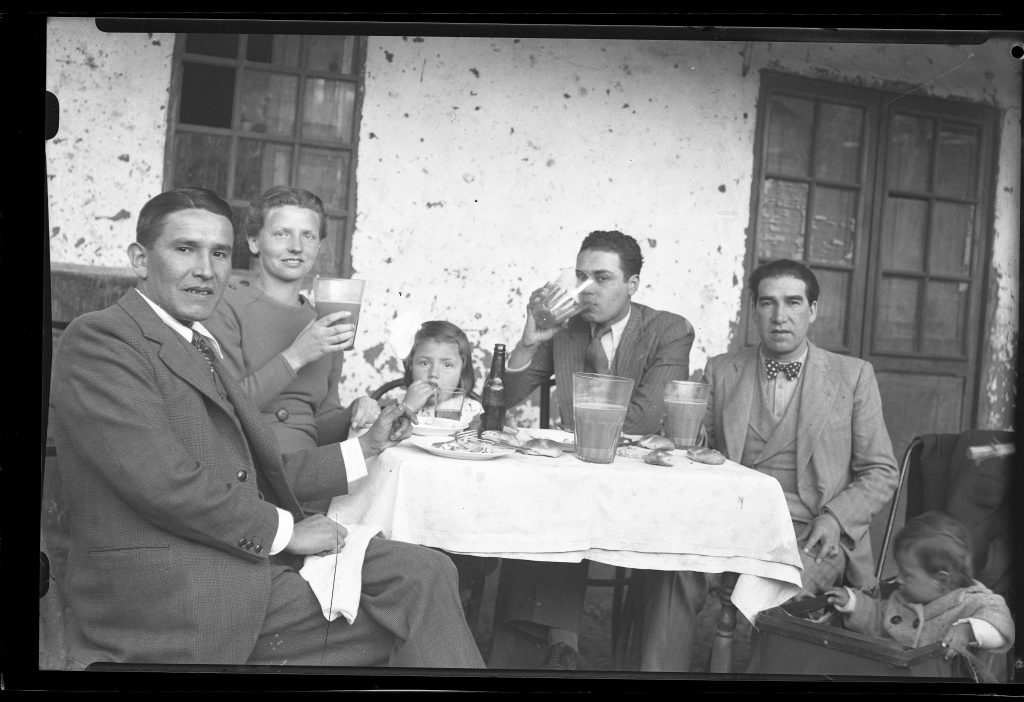

Unlike Lima—a conservative backwater during the early to mid 20th century—Cusco saw an unprecedented cultural renaissance thanks to a vastly improved transportation system. Several railway lines put an end to the isolation in which the city had existed since colonial times, one connecting the city to Arequipa and the Pacific through the port of Mollendo, the other, established in 1908, to Buenos Aires, the Atlantic, and Europe. Indeed, the route between Cusco and Buenos Aires at the time was better and faster than the tortuous roads across the Andes leading to Lima, which were often impassable during the rainy season and which even in the best conditions could take up to a week to traverse. Significantly, at the time, Cusco was more “modern” than Lima thanks to the arrival via Buenos Aires of European news, magazines, fashion, and new political ideas, as well as an influx of foreigners. Ramón Gutiérrez, Elizabeth Arce, and Graciela Viñuales’ important 2009 study Cusco-Buenos Aires: La ruta de la intelectualidad americana (1900-1950) traces how faster connections between Cusco and Buenos Aires (and thus Europe) allowed Cusqueños to gain access to international newspapers, journals, and magazines, and to follow new intellectual routes. Argentineans, Germans, Italians, Arabs, and other foreigners also contributed to the increasing cosmopolitanism of the city, settling there and establishing different industries in the area. They too posed with their families for very formal portraits in Martín Chambi’s studio, and they also asked him to photograph them outside of the studio as we see below.

He also photographed street scenes, market scenes, and the daily hustle and bustle of life in the city.

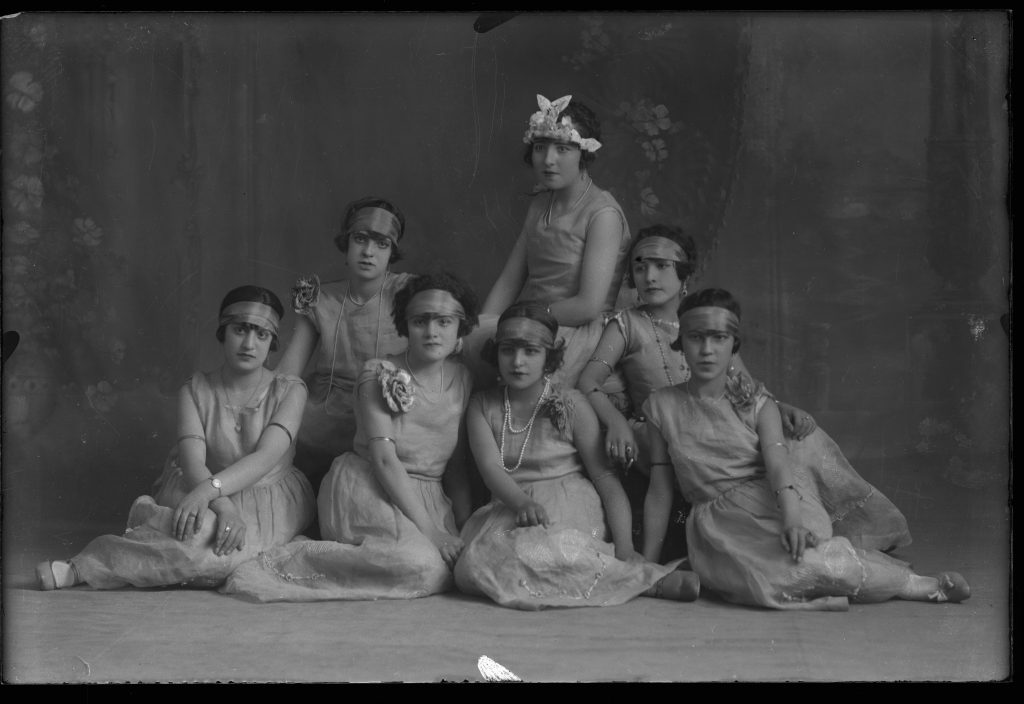

Women in particular avidly followed the fashion of the 1920s and 1930s thanks to the arrival of various magazines from Buenos Aires and Europe. Like Cusqueño men who imitated English dandies in their look and affect, women wore the dresses and evidenced the flair of flappers.

Chambi’s photographs register the incursion of modern forms of subjectivity in Cusco; his portraits evidence the cosmopolitanism, exquisite whimsy, and also the profound need for representation on the part of Cusco’s women.

Modern woman in the studio. Photo: Martín Chambi, n/d.

Modern woman in the studio. Photo: Martín Chambi, n/d.

Modern woman in the studio. Photo: Martín Chambi, n/d.

Modern woman in the studio. Photo: Martín Chambi, n/d.

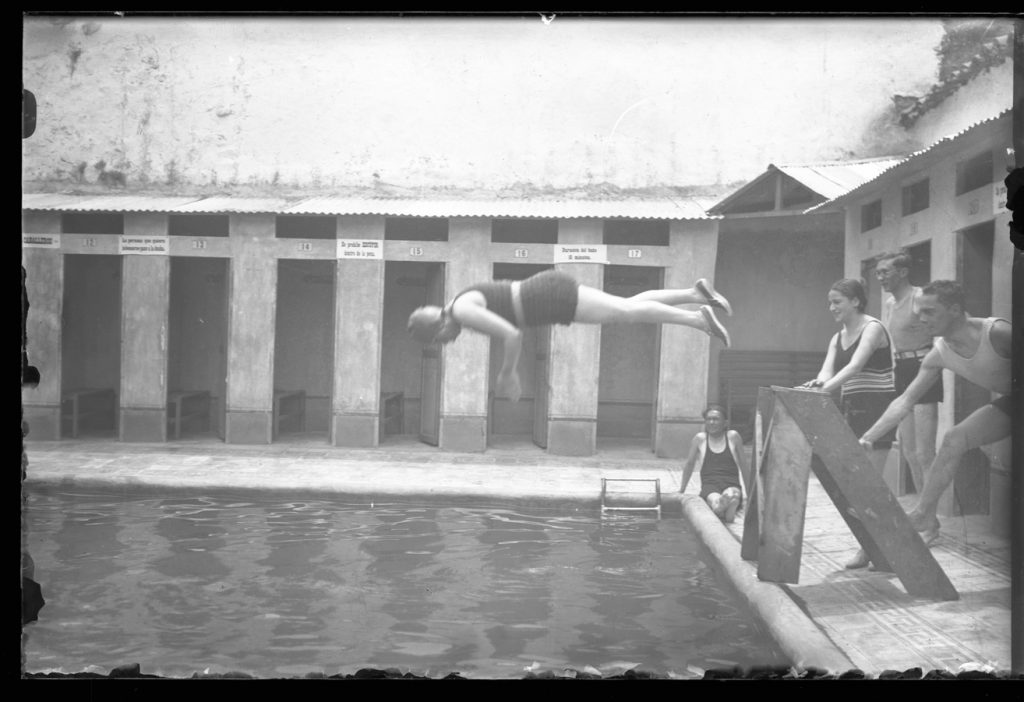

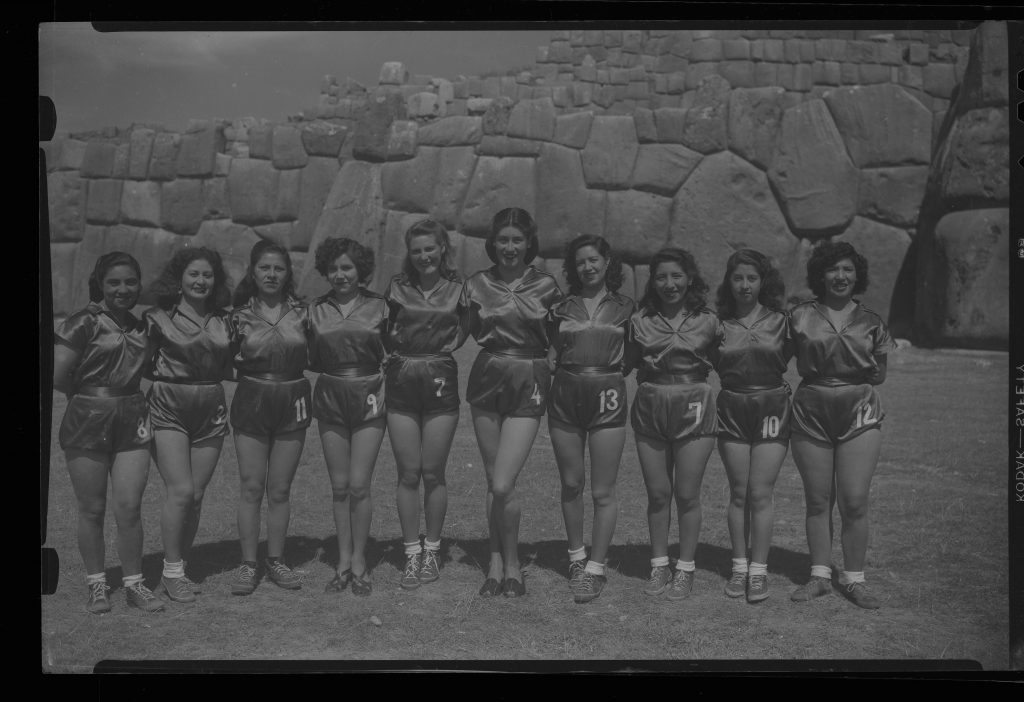

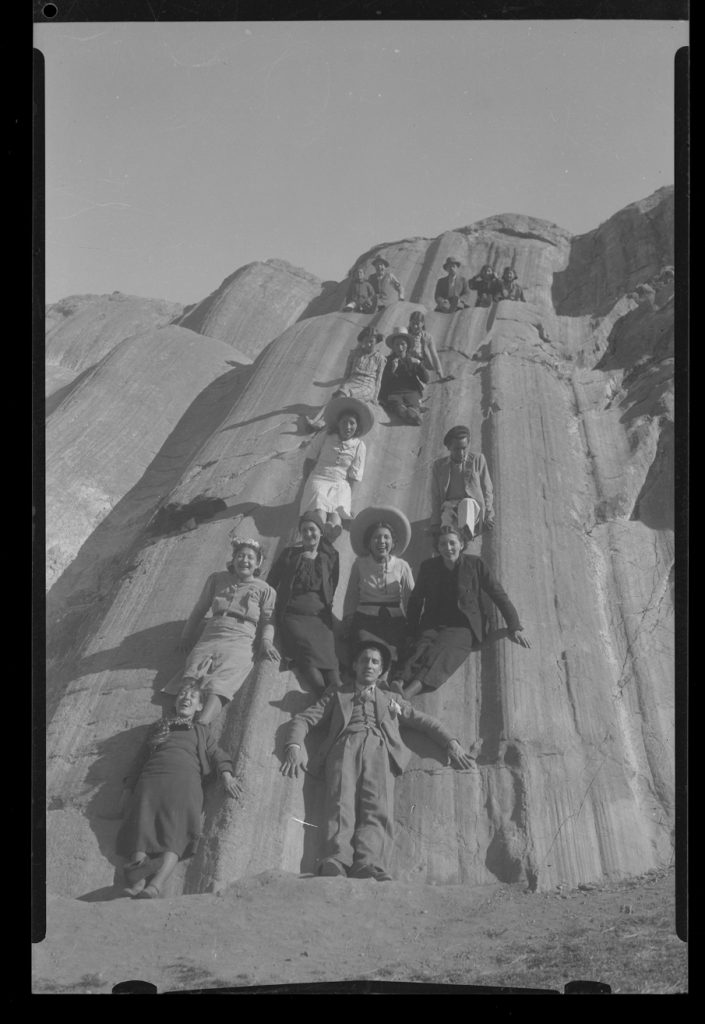

Chambi’s photographs register the incursion of modern forms of subjectivity in Cusco; his portraits evidence the cosmopolitanism, exquisite whimsy, and also the profound need for representation on the part of Cusco’s women. They delighted in flaunting their new freedom before his camera in the studio. He photographed them in the streets flaunting a new car or in their team uniforms, and there is even one image of a woman in the air as she dives into a pool. He photographed women with their friends on the rock slides at Sacsayhuamán, on Sunday outings, showing off their first car, or working in the newly established telephone exchange in the city, and he even photographed a female bullfighter. This can be seen in the photographs below, which were scanned for the first time as part of Teo’s and my collaboration.

Posing in plaza with new car. Photo: Martín Chambi, n/d.

Diving. Photo: Martín Chambi, n/d.

Female sports team. Photo: Martín Chambi, n/d.

Photo: Martín Chambi, n/d.

Photo: Martín Chambi, n/d.

Chambi also delighted in photographing Cusqueña‘s performative flair and their love of carnival and dress up, as we see in the images that follow:

Martín Chambi celebrating indigenismo. Photo: Martín Chambi, n/d.

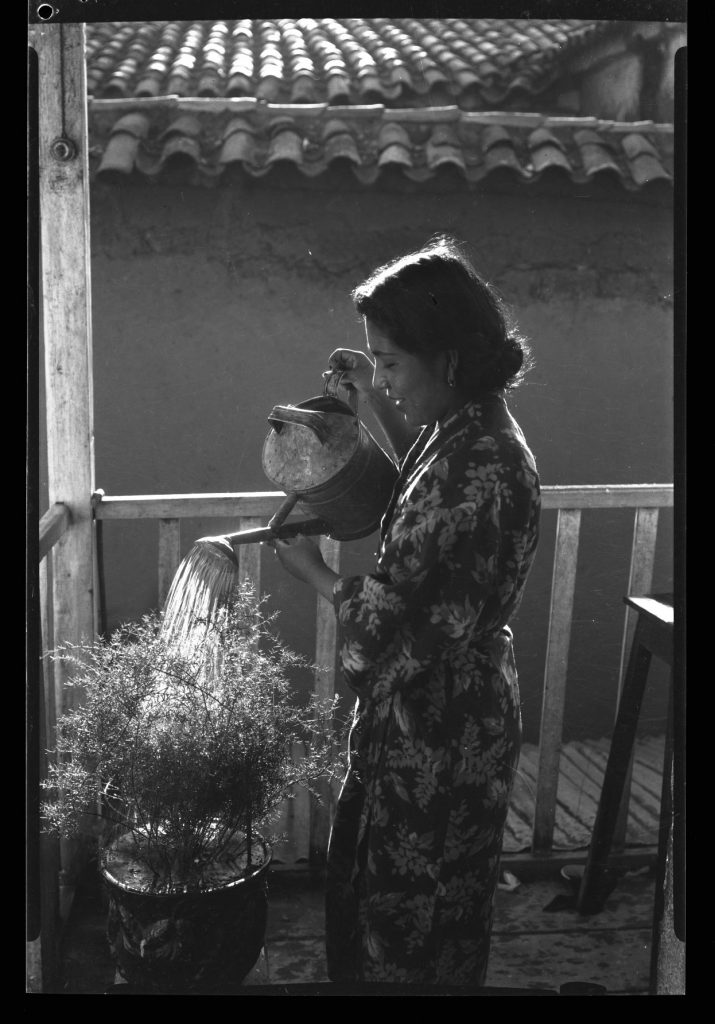

Throughout his life, Chambi took numerous self-portraits as well as photographs of his friends and family. In the image below we see Celia Chambi, Teo’s mother, at home in the early morning light.

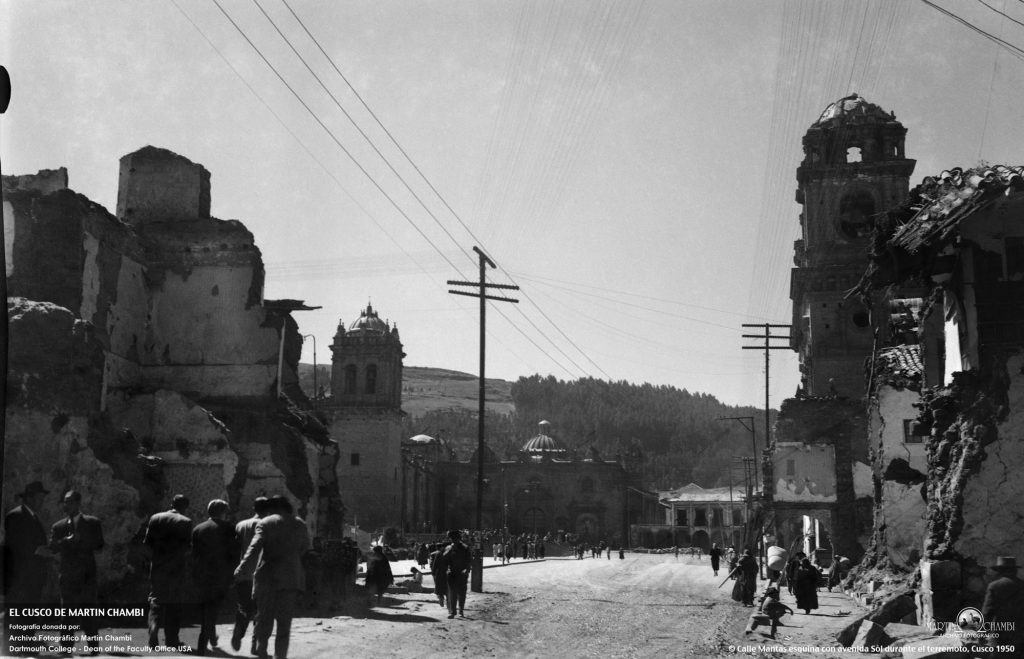

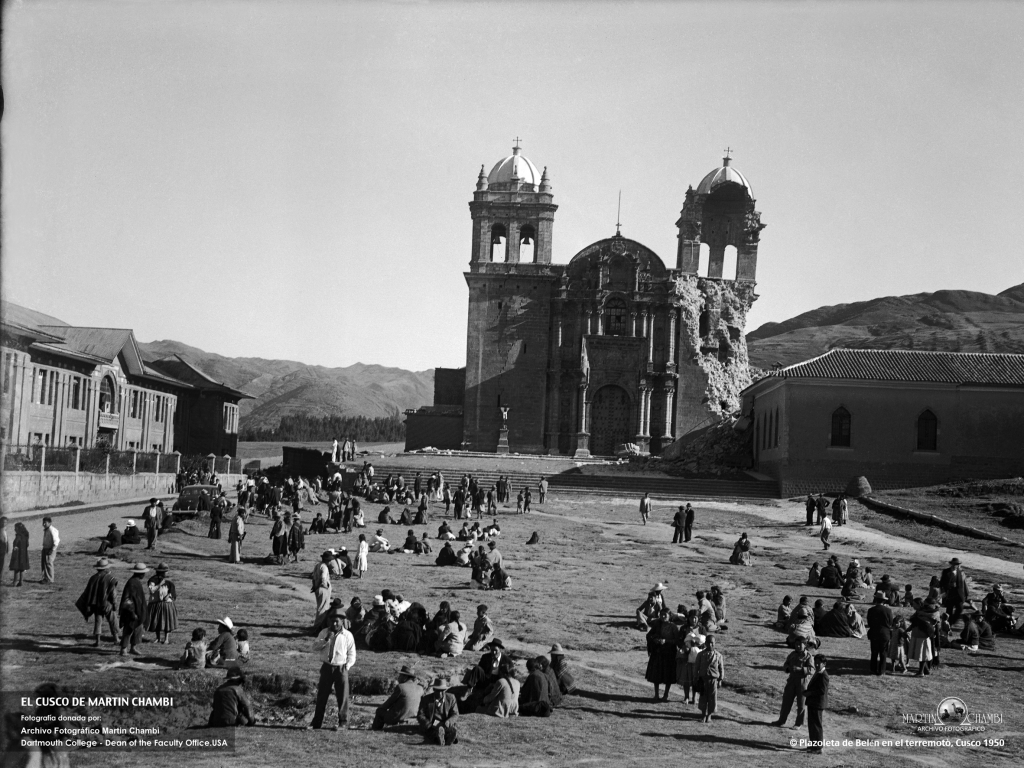

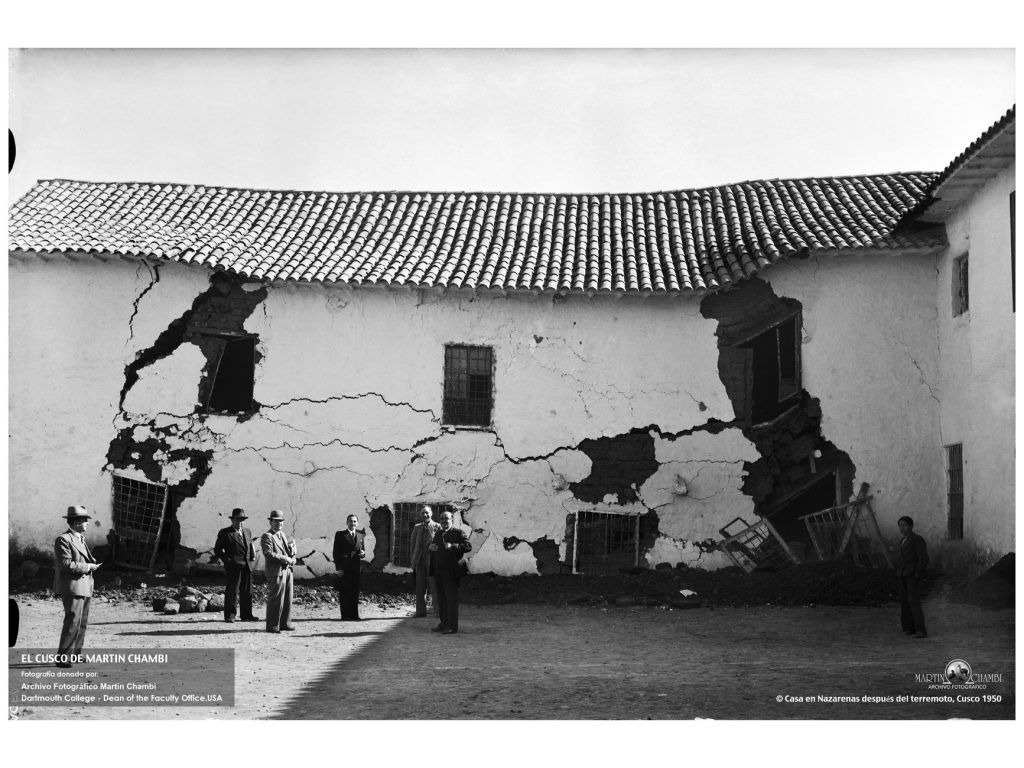

Chambi photographed Cusco as the city was sadly becoming a ruin once again. The photograph he took of the intersection of Calle Mantas and Avenida Sol during the 1950 earthquake could not be more telling of the devastation. Local lore has it that Chambi took it as the massive earthquake was happening. Significantly, these photographs later served to guide the city’s reconstruction.

Calle Mantas en el terremoto

Belén Plaza during the earthquake. Photo: Martín Chambi, 1950

House in Nazarenas after the earthquake. Photo: Martín Chambi, 1950

The devastation caused by the earthquake was coupled to a period of unparalleled growth. Cusco went from 26,936 inhabitants in 1912, to 37,000 in 1920, 54,631 in 1940, to well over 500,000 today. This growth, coupled with the need to rebuild large parts of the city post-earthquake, and the interest in all things Inca across Peru and the Southern Cone, led to the emergence of new—neo-Inka—forms of architecture.

Beyond Cusco and the Southern Peruvian Andes, Chambi himself also followed the new routes that had opened up. He exhibited his work in Argentina and Chile to great acclaim. His photographs of the pre-Hispanic archeological discoveries in Cusco and its vicinity were avidly reproduced in important magazines in the Southern Cone and contributed to the craze for all things Inca of the times and the emergence of a neo-Inka style that I will discuss below. But he gained full international recognition only after his death in 1973 when anthropologist and photographer Edward Ranney, with the support of the Earthwatch Foundation, spearheaded work to preserve and catalogue part of his archive. Working with a team, Ranney positivized and digitized 5,000 glass plate negatives in 1977. This effort culminated in a major retrospective and exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City in 1979, which led to the international appreciation of the artistic, cultural, and historical significance of Chambi’s œuvre and the establishment of the Martín Chambi archive in 2005. In 1993, the Smithsonian Institution published Martin Chambi, 1920-1950—a translation of the most important study to date. With a foreword by Mario Vargas Llosa and introductions by Edward Ranney and Publio López Mondéjar, it is often the only book on Martín Chambi to be found in bookstores in Cusco.

Besides making Martín Chambi’s oeuvre renowned, Ranney’s efforts, as well as the MoMA exhibition, opened the way to a wider interest in early Andean photography. A welcome effect of Martín Chambi: Photographs, 1920-1950 was the attention that this book drew to an important cultural manifestation across the Andes that was in danger of slipping into oblivion. An unintended effect, however, was that it has led to the current fetishization of glass plate photography at the expense of the work done later with film and digital cameras. Indeed, Chambi adopted the newer cameras, but he never warmed to the new medium, and to date, the emphasis has been on preserving and digitizing the glass plates since they allowed for the storage of greater amounts of information and resolution than was possible with the smaller format cameras coming into vogue from the 1950s onward. Indeed, his career declined with the passing of the era of large format cameras.

Today, the Martín Chambi Archive holds more than 35,000 glass plate negatives. The archive includes everything he produced in his studio in Cusco on Calle Marquez as well as photographs by his son Victor and his daughter Julia—a talented photographer in her own right and key in preserving her father’s archive. It does not hold the photographs he took in Sicuani as a newly married man where he opened his first studio. Since he took over the studio on Calle Marquez in Cusco from renowned photographer and dandy Figueroa Aznar, he most likely inherited some of Figueroa Aznar’s photographs, just as the Max T. Vargas studio in Arequipa where he was an apprentice probably absorbed some of Chambi’s work. Indeed, as with many studios across the Andes and elsewhere, before copyright and authorship claims dominated the artistic landscape, photography studios functioned as communal enterprises. Much in the same way that the seal of the master was used by the entire studio during Cusco’s Golden Age of painting in the colonial period, Chambi’s studio and the seal “Estudio Martín Chambi” included not only the work of the master but also that of collaborators, various apprentices, and of Victor and Julia. After his passing, the archive was held by Julia, his lifelong and steadfast collaborator, who, shortly before her death, appointed Chambi’s grandson, Teo Allaín Chambi, to be its director. Given that Teo and his son Andrés Fernando are also photographers, the archive will at some point be the repository of four generations of Chambis who continue to photograph the city of Cusco—a city which has repeatedly been destroyed yet has risen from the ruins time and again and has been preserved by that most ephemeral of mediums: photography.