Having experienced the different stages of precarity and inaccessibility—and even invisibility—affecting many of Cusco’s collections, I became ever more convinced that archives truly only achieve their full potential and come alive when they are accessible to and in dialogue with the community in which they emerged. In the case of Cusco, it is particularly important—even urgent—as I pointed out earlier, to establish a dialogue with the community while elders can still help reconstruct the context and subjects photographed, thus giving personal and local information that would otherwise be lost. Without that historical “metadata,” photographs quickly become ghostly and collections become interesting and important in other, but more general, ways. In Chambi’s archive there are, for example, photographs of glaciers that are now being consulted to study the effects of climate change in the Andes. Luckily, the Chambi family and others were able to identify the glaciers in the photographs, thereby giving scientists an important measure of their present retreat.

Chambi’s work is regularly shown in the global art circuit but it is largely unknown in Cusco.

Given the ups and downs of archives in the city, I was lucky to find the Martín Chambi archive. It was a vibrant space, with a director fully cognizant of the value of the collection and committed to the preservation and diffusion of his grandfather’s work. Indeed, Teo was eager to collaborate and curate the city-wide exhibit in Cusco that I proposed to him because, as I pointed out above, Chambi’s work is regularly shown in the global art circuit but it is largely unknown in Cusco. Sadly, Cusco is a worldwide tourist destination and photographed millions of times a day by visitors, but the work of one of the city’s greatest photographers who worked tirelessly to achieve this visibility was largely unknown. As Teo and I discussed how to proceed, we settled on continuing the digitizing of the glass plates in the collection and—in a shorthand of sorts—to put on “a monumental event for a monumental city.” We therefore decided to enlarge 32 key photographs Chambi had taken of Cusco before the post-1950 earthquake reconstruction of the city under the aegis of modernization. We decided to place the installations all around the city—from the Plaza de Armas all the way out to San Sebastián (once the countryside visited on Sundays), from beloved Plaza Regocijo in the historic center (so called for its trees that attracted many birds) to the Almudena Cemetery where many Cusqueños are buried, and to Cusco’s only movie theater during Chambi’s time, now a hotel. The enlargements (3 x 5 meters) were of high-quality photographic paper with ultraviolet filters and water resistant to protect them from the radiation and rains. When the exhibit was about to go up, two technicians flew to Cusco from Lima to glue the enlargements onto framed heavy sheetrock set up on metal pedestals so that the installations could be free standing.

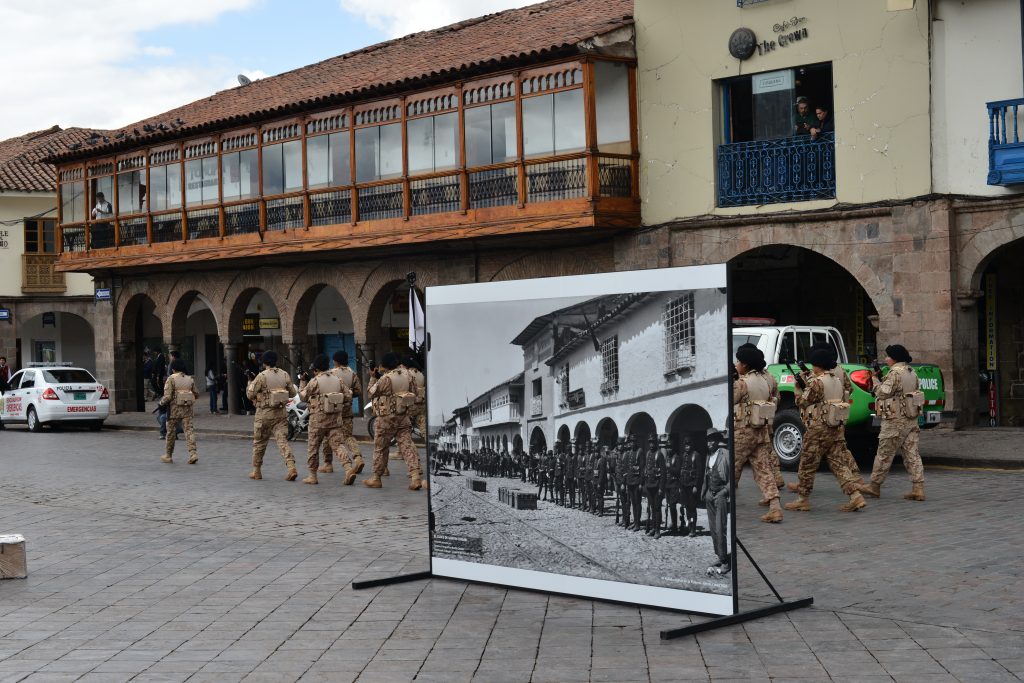

We aimed to create a truly public exhibit and have people from all walks of life participate—especially those who would not normally enter an official government space, much less go to a museum. Equally important, we imagined that putting the installations up in the streets within arm’s reach of passersby would immediately interrupt—and even cause—a visible break in the space and time of the city. Indeed, the jarring contrast between the two cities, Cusco today and the city almost 100 years ago, would lead to a long overdue discussion regarding the needs of preservation and those of tourism. We also hoped to encourage Cusco’s residents to “intervene” in the exhibit in any way they chose—whether it was taking selfies in front of the images or covering them with graffiti. Additionally, we invited Julio Pantoja, a well-known photographer and academic from Tucumán, to document the event and people’s reactions and interventions. To provide further contrast between the city Chambi had photographed and the Cusco people know today, we asked two photographers to film the spaces where Chambi’s installations were going to be set up.

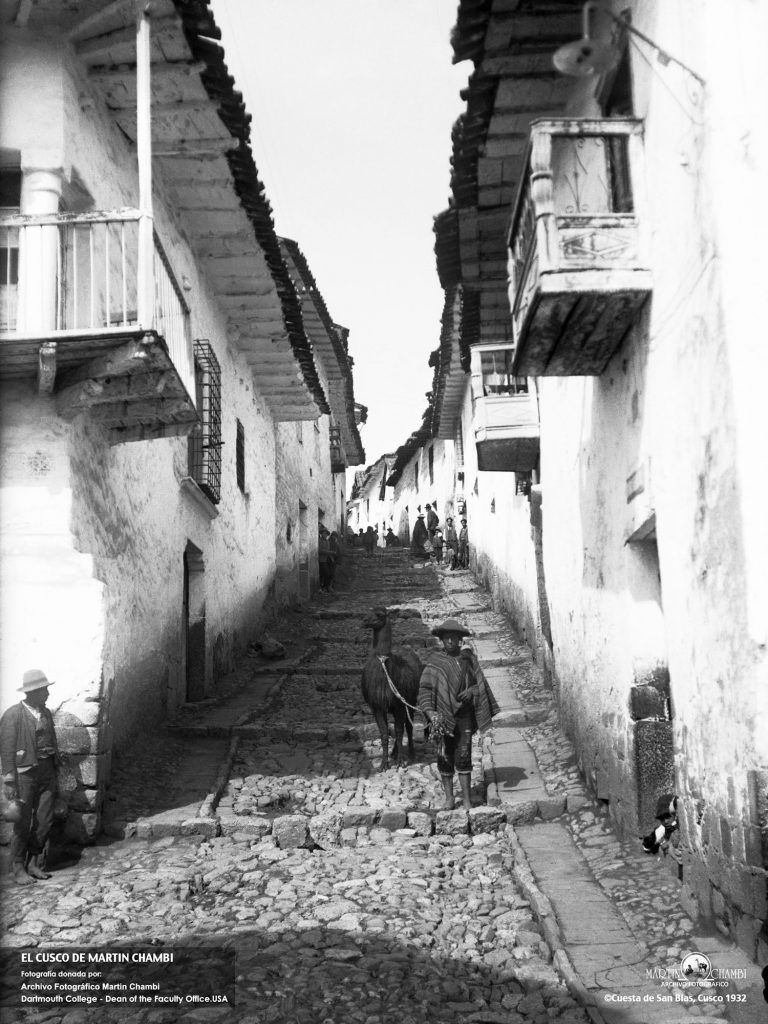

One hurdle we encountered, given the exponential growth of the city since Chambi had photographed it, was identifying the exact spot where some photographs had been taken. The district of San Sebastián, for example, once on the outskirts of the city, was where Cusco’s residents used to go for a Sunday picnic. Today, it has been absorbed by the city. We realized that Chambi had often risen early, before anyone was out, or that he had taken his shots in the middle of streets that are now congested. Since we could not block traffic and wherever we had other constraints, we hung the images on walls as close to where Chambi had originally taken them as we could. In the famous Cuesta de San Blas, for example, we had to hang the enlarged photograph high up on an abandoned building, but to great effect since passersby immediately realized the photograph was of the very street they were about to climb. The contrast between the now busy intersection and Chambi’s photograph of the man descending the stairs of the Cuesta de San Blas with his mule on what had once been a peaceful street was startling. The tearing out of the stairs on the streets, which leads up to the oldest and most traditional part of town, had transformed it into a veritable nightmare for cars and pedestrians alike and made this intersection one of the city’s worst.

Julio Pantoja photographing exhibit. Photo: Silvia Spitta, 2014.

Between September and October, 2014, then, passersby were suddenly confronted with the stunning black and white photographs in streets and plazas across the city and all the way to the outskirts. We had no idea how the exhibit would be received or what impact, if any, it would have since something of this magnitude had never been done in the city before. Moreover, Teo and I had never organized such a big event before, so we did not know what to expect. Therefore, while we anticipated some things, we could not foresee others. In the end, we were pleased by the sheer enthusiasm with which “El Cusco de Martín Chambi” was received and the many discussions that took place every day, all day, in front of the images during the month the exhibit was up. While the local newspapers barely noted the exhibition, national news, television, and radio did. Peru’s leading newspaper, El Comercio, estimated that 80,000 people viewed the exhibition.

It is unclear how El Comercio arrived at that number, but it quickly became clear to us that the exhibit had massive appeal and was having a great impact. Every day, everywhere, we encountered people standing in front of the images, studying them and discussing them with others. Veritable tableaux of the city, Chambi’s photographs embraced the great diversity of Cusco, as well as the nuanced continuum between rich and poor, urban and rural, peasants in the city and landowners in the countryside. Indeed, the people standing before the installations were no less diverse than those that Chambi had photographed almost 100 years before. Many were people who would normally never have entered a museum. When they repeatedly asked us for a map of where we had placed the installations around the city because they wanted to see them all, Teo’s son Andrés Fernando quickly set to work. In one of the images below, we see two women consulting the map he created and which we handed out in the streets.

Photo: Julio Pantoja, 2014.

Photo: Silvia Spitta, 2014.

Photo: Julio Pantoja, 2014.

Women studying the map. Photo: Silvia Spitta, 2014.

We observed day after day how bystanders engaged with one another to reconstruct the changes Cusco has undergone, how they tirelessly discussed or worked to reconstruct past events in the city together. Some would go home and consult elders about the location and appearance of certain streets and buildings and then stand in front of the images and share with others what they had learned. Of particular interest was how the buildings of the city had been rebuilt after 1950: where Inca walls had been moved, where new ones were erected, and where the Inca served as the conceit I have called neo-Inka. People’s concerns around the displacement, destruction, and reconstruction of Inca walls, then, reflected their interest in how the city had been rebuilt post-1950 when the colonial city was rebuilt once again, but this time with an eye to highlighting the Inca legacy, which was becoming a magnet for tourism. They noted neo-Inka flourishes wherever Inca walls had been reconstructed and even were shocked to see walls erected where formerly there had been none. In some cases, stone foundations and walls were built out of cement blocks made to look like Inka stonework; facades were “Inkaized,” and the typically dark adobe interiors of colonial architecture, to quote a tour guide, were replaced by “noble” materials such as cement and glass. More importantly perhaps, electric lighting lit up formerly dark interiors. As this guide commented nostalgically, the “historic” city was made to look like the colonial one, but she somehow felt that the essence of the city had been “hollowed out.”

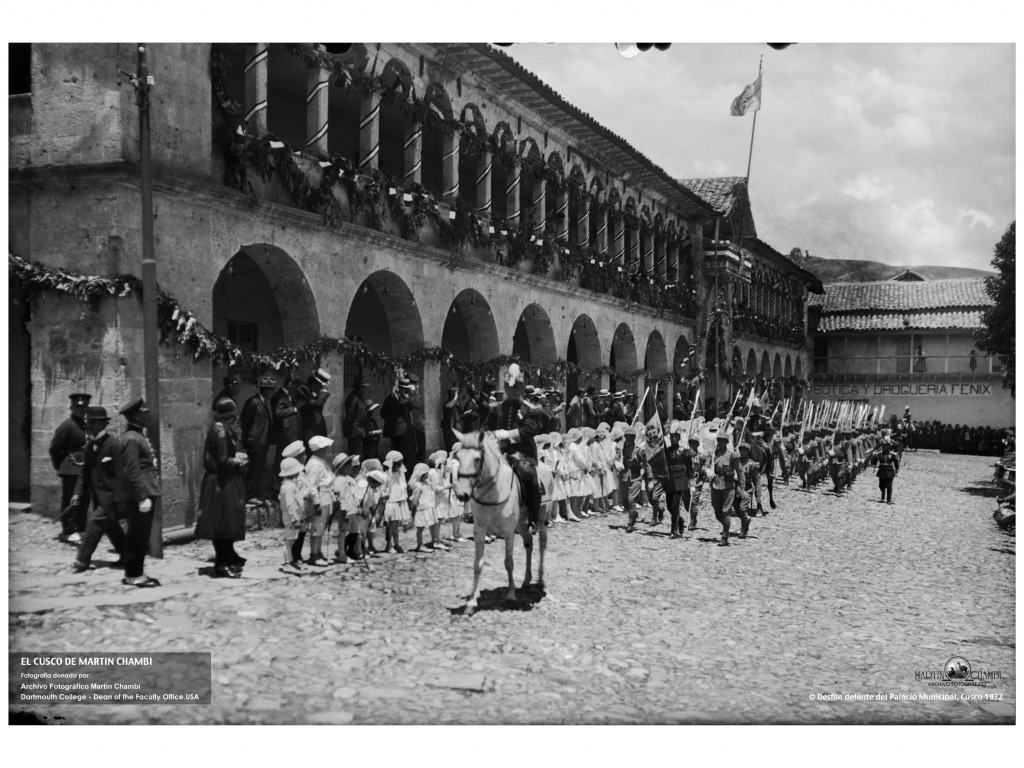

City hall, for example, in Chambi’s photograph taken in 1932, shows a triangular wooden gable over the main entrance.

Procession in front of the Palacio Municipal. Photo: Martín Chambi, 1932.

Photo: Martín Chambi, 1932.

When the structure was rebuilt after the 1950 earthquake, it was given an angular façade reminiscent of Inca architecture, designed to appeal to tourists.

When viewed from a higher vantage point, this structure was a façade much like that of a Hollywood set. An artist comparing Chambi’s photograph with the contemporary building pointed out that the new windows of the building were framed by Inca stonework, whereas the simpler colonial building had no such decoration. My landlady, a tour guide quick to blame tourism for the perceived “destruction” of the city, realized to her utter surprise that Chambi’s photograph of the plaza showed that an Inca wall had been erected there after the earthquake. Today, many five-star hotels also cause controversy in the city when they move Inca walls and otherwise alter ruins as they are being erected. In these multiple ways, destruction has led to creative license, and architects now freely “Inkaize” the city across the historic center.

Chambi’s photographs also helped correct the nostalgic notion that attributed all of the changes to the perceived destructiveness of tourism. One installation that insistently drew the attention of passersby was “Capilla del Triunfo,” which shows theft at work in the most public yet invisible manner. Placed by the chapel, Chambi’s enlarged photograph clearly showed that a statue is missing today in the middle niche of the chapel next to the cathedral. While theft has taken many surreptitious forms in the city, this glaring example shocked people repeatedly.

This ongoing confusion of Inca with pre-Inca, evident in the neo-Inka style, also befuddles outsiders who arrive in search of “real” Indians when in fact there are but fluid identities, and identity has to be understood only ever as a performance. This confusion became evident long ago at a time when a statue, variously known as “American redskin,” “Apache,” and “Indian warrior,” crowned the fountain at the center of Cusco’s main plaza. It had been there for decades and no one quite knew who had placed it there or when.

Chambi, of course, photographed the “Apache.” In this iconic photo, which we set up in the Plaza de Armas, you see the statue of the misplaced Native American and also the shadow of Chambi taking the photograph. The church clock shows that it was 4:20 PM.

The origin and reason for the “Apache” sculpture is a mystery to this day and was much discussed in front of that installation. Many urban myths were revived, one unlikelier than the next. The story I garnered is that, thanks to the emergent sensibility of indigenismo, the “Apache ” became a symbol of the profound ignorance around indigenous culture that prevailed at the time and that had made possible the confusion of Native Americans with Peruvian Indians. Critics began to call for the misplaced Indian’s removal. According to Teo, however, the statue of the “Apache” was kept there until the 1960s, when Cusco’s indigenistas toppled it. Reportedly they were Aníbal Acurio and Prof. Manuel Jesús, who were detained but released for lack of evidence. After the toppling of the misplaced statue, Cusco’s highly symbolic center remained empty until 2011, when a gold fiberglass statue of Inca Pachacutec was placed there for the Inti Raymi. This was thanks to the indigenistas who, with great marketing savvy, revived a ritual celebrated on winter solstice in honor of the sun, which had been banned during the colonial period. As I discussed earlier, they reinvented the tradition and re-presented the Inca festival with local actors and involved thousands of people from the city and surrounding communities. The indigenistas were so successful that the Inti Raymi has been celebrated annually since its first re-enactment in 1944, and it now attracts thousands of visitors. Thanks to this, the gold fiberglass Pachacutec remained in Cusco’s Plaza de Armas despite renewed protests by then-Minister of Culture Juan Ossio. Luis Florez, Cusco’s former mayor with whom we negotiated all the permits for the exhibit, had it finally replaced with a stately bronze statue.

“Inka” Performance. Photo: Silvia Spitta, 2014.

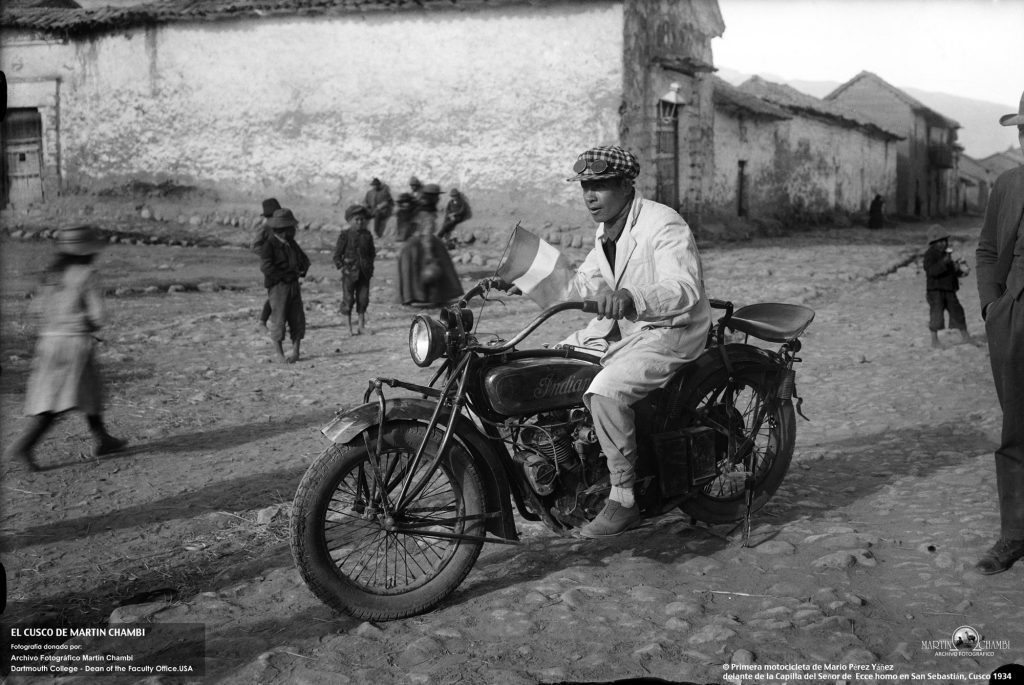

The story of the statue in the Plaza de Armas is somewhat convoluted and inflected by urban myths, but it is a significant index that poignantly follows the trajectory of the neo-Inka revival, which transformed the Inca into the neo-Inka aesthetic and politics that I outlined earlier. But this was not the only confusion regarding indigeneity. Indeed, already in 1930 Chambi documented the arrival of the first motorcycle in Cusco. It too happened to be a misplaced “Indian.” “Mario Pérez Yáñez’s first motorcycle” shows a friend of Chambi’s wearing an overall to protect him from the dust, riding down the street in San Sebastián while little kids play in the street and watch with amazement. The brand of the motorcycle also happened (perhaps not altogether accidentally) to be “Indian.”

Created by a US company, the “Indian” was one of the earliest models of motorcycles made. It continues to be produced, most recently with the unfortunate model name, Indian Chief Dark Horse. The implicit irony of a motorcycle branded “Indian” arriving to Cusco as a symbol of modernity was perhaps not lost on Chambi, who went on to take a famous self-portrait riding that motorcycle.

In the above photograph, the motorcycle first draws your attention, then the eye shifts to the Peruvian flag on the handlebars, and then you focus on the children looking at the motorcycle as Mario Pérez Yáñez rides by them. In this staging, it is as if modernity were leaving the children and the dirt road behind, as Jorge Coronado has argued. When we placed Chambi’s photograph in the plaza close to that street, however, people realized that even where it arrived later, modernity has engulfed everything; the children staring at the motorcycle are also looking into the future transformation their city would undergo.

Photo: Silvia Spitta, 2014.

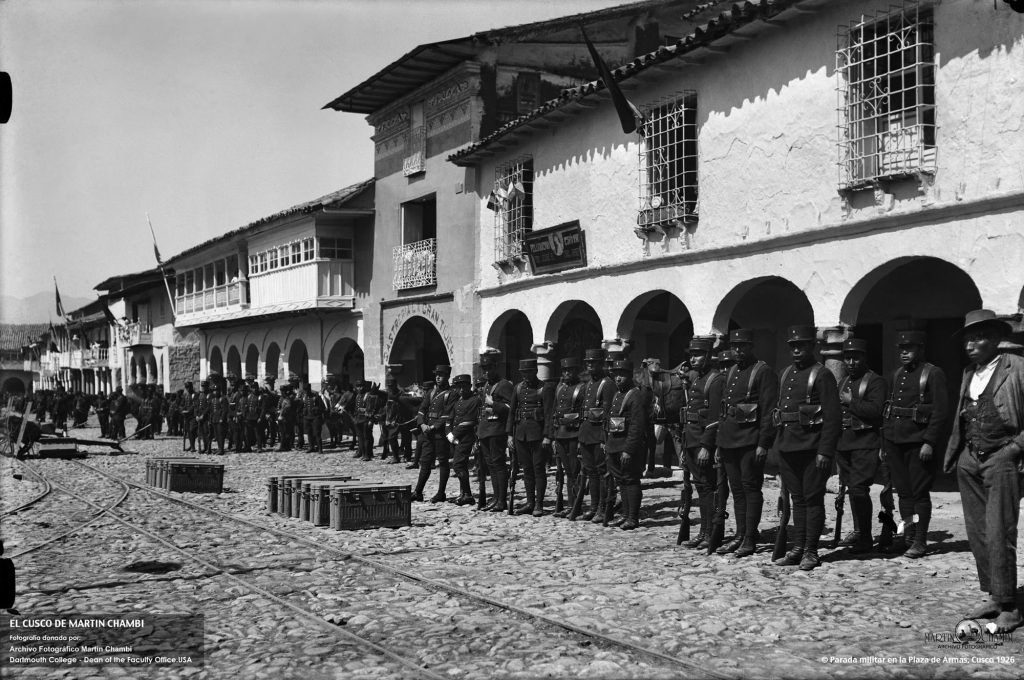

The enlargements, then, trained people to look at photographs with great care, not only comparing the architecture and streets then and today, as if putting together a puzzle, but also helping them realize the intricate nature of Chambi’s compositions. A photograph that repeatedly drew onlookers into dialogue with one another was this one of Plaza San Francisco during a military parade. People commented on the tearing out of the tramlines that had formerly connected the different parts of the city, and which led to the overwhelming of the city by cars. They also noted the poverty of the peasants forced into conscription made evident in their makeshift shoes, which could now be seen in the enlarged photograph.

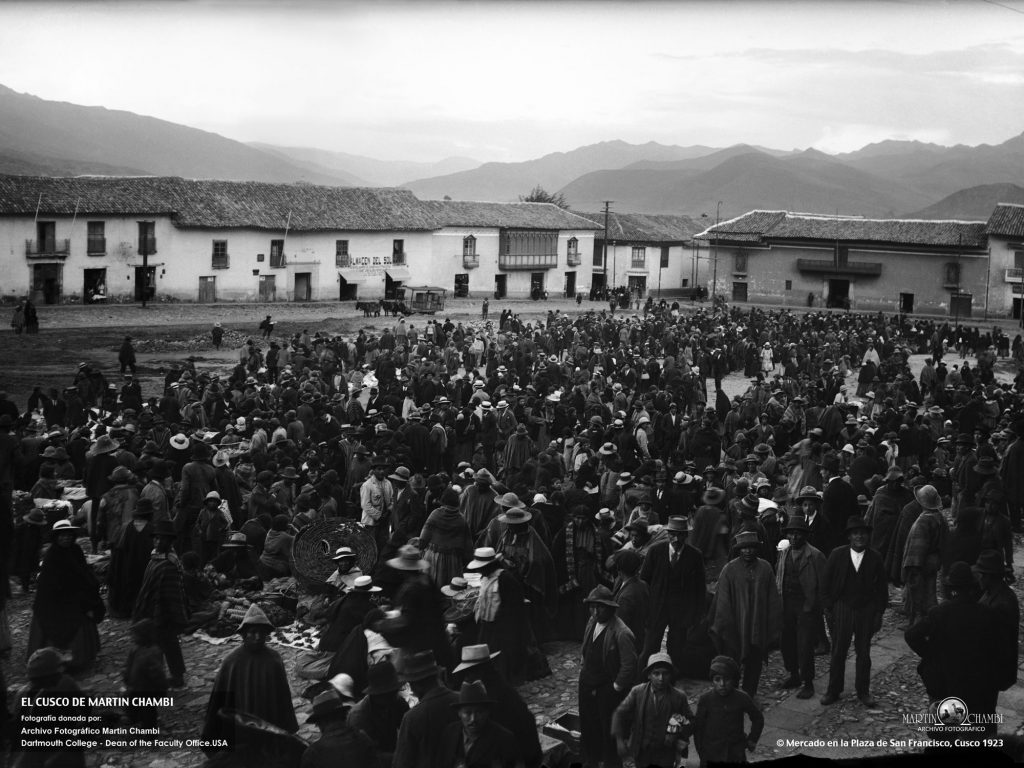

The installations thus allowed people to detect details in Chambi’s photographs that get lost in smaller size reproductions. Whereas in a postcard size reproduction the street market at Plaza San Francisco tends to become a blur, in the enlargements, the scenes within scenes that make up Chambi’s compositions became readily apparent.

His shots of the cathedral and central Avenida El Sol in ruins, or the Plaza Nazarenas and Plaza Belén, taken shortly after the earthquake, show the extent of the 1950 destruction and the pains taken to rebuild the convents lining the famous plaza at the center of the historic San Blas district (now controversial five-star hotels). Teo’s statement that the exhibition had “broken the eye” refers to the shock of viewing the enlarged photographs, which allowed people to contrast the city in ruins with how it has been rebuilt. Furthermore, it allowed them to contrast the pollution of today’s city with the clear air in Chambi’s photographs. The exhibition refocused Cusqueños‘ tendency to forget the city’s different historical layers, and the ways in which it was being both preserved and destroyed over time. Viewers realized that there is no “real” Cusco, just as there are no “real” Indians, only layers and layers of historical entanglements, compromises, and transculturations.

Alongside the nostalgia that many expressed for the bygone city, other kinds of abandon become evident. The historic center has become almost inaccessible to locals because it is too expensive. Many older families have had to sell their homes and move further to the new part of town. Many, like Teo himself, avoid the center because of the traffic, lack of parking, intersections blocked by large tour buses, and other obstacles. They avoid expensive cafes and restaurants full of tourists, preferring more local, if less “traditional” places. Or they recoil at the sight of the discos and drug scene on Avenida Suecia that now attract adolescents and expose them to more permissive foreign mores popularized (or enabled?) by interactions with tourists. Gigolos, or bricheros as they are known, seduce unwitting gringas for sport, to make an easy buck or to marry out of Peru.

Statue of Chambi amid visual trash. Photo: Silvia Spitta, 2014.

Underlining the tension between old and new that runs through the indigenistas’ work and thinking, the exhibit offered a sharp contrast between the city of 50,000 in the 1950s and the ramshackle metropolis of over 500,000 today. It was not surprising, then, that the subtext of most people’s comments touched on pollution: visual, auditory, olfactory. Other than in the historic center, which is carefully protected, the surrounding city is a veritable jungle of signage. Strident political propaganda exists next to loud advertising. A symbol of this visual pollution is the photograph I took of Chambi’s statue amid all the advertising in the city today.

Since there were regional elections taking place, the mayor and others were afraid the installations would be used as billboards for political propaganda. In San Sebastián, where we had placed 3 installations in the plaza, local officials became afraid of vandalism and wanted to protect them. To our utter dismay, they ordered a fence built around them and on rainy days even had a tarp erected above them. In this way, they prevented people from touching or viewing the images up close and also foreclosed the possibility of any interventions, which we in fact, welcomed. We repeatedly insisted that these barriers be taken down, but to no avail. The Museo Inka where we had also placed an installation went even further: they simply took it indoors and refused to display it outside the building.

Barriers in San Sebastian. Photo: Silvia Spitta, 2014.

In this photograph, a woman—most likely someone who works in the museum—is attired in a traditional dress and flamboyantly strides by the enlargement that we had placed outside the Museo Inka but which they had moved indoors. The drive to protect and frame the gaze, then, was too great in the face of a long-standing tradition of associating art with institutional forms of “enshrinement.” In the end, the experience in the city proved everyone overcome by a protective zeal wrong. “Enshrinement” did not prove necessary, and we either witnessed or were told about incidents where the public protected the images in ways that bespoke an “owning” of the exhibit and perhaps too, a city so overrun with tourists and their cameras was now showing off the mastery of one of its own great photographers.

Altogether unintended, the shrill political propaganda of the upcoming elections made Chambi’s photographs stand out all the more. The contrast highlighted how stressful the city has become jammed with traffic,cars honking incessantly, and exhaust choking the air, making it even harder to get enough oxygen at over 10,000 feet above sea level. Almost like the monoliths at Sacsayhuaman that tower over the city, the photographs in the exhibit continually reminded people of an era when time moved slower, the air was cleaner, and the world was more wholesome. They seemed to transport passersby into a dream space that perhaps had never been fully articulated in the city. As a taxi driver told me, “That past time was so safe and wonderful. I can imagine my ancestors walking those streets. Now it’s just all about survival. We work day and night and can’t even make ends meet.” The nostalgia that the photographs elicited in viewers reminded me of our endless fascination with the black and white of Hollywood noir. In these films, despite the danger and crime, the world looks less cluttered and the air cleaner (and the people more well to do, of course). Unlike other towns across the Andes that have remained relatively stable over time, Cusco’s massive growth has shattered the past. The sharp focus and dignity of Chambi’s photographs therefore arrested the eye and brought the imaginary veneer of this idealized past into sharp relief.

Because it was sited within arm’s reach and often in people’s way around the city, the exhibit created many possibilities for onlookers to engage with the exhibition in their own way, as we had hoped. Local and international photographers, as well as casual onlookers, photographed the installations. The city, once again, became a city of photographers. We initially experienced the exhibit’s mass appeal during the event hosted by the mayor of the district of San Sebastián before the three installations were set up in the plaza. In one of the images below, a local woman is pointing out with great delight where the school, chichería, and police station had formerly been, as well as the house where she had once lived. While in other contexts she would have been called a native informant, here she was in her element. It was moving to see how she instantly garnered the attention and even awe of those around her because she was able to explain where the street is today and what the buildings were. Indeed, Teo and I had wandered about for hours in San Sebastián before we were able to identify the exact location where Chambi had taken the shot.

Julio Pantoja luckily caught this first moment, which was repeated every day in the city as people became invaluable informants across ethnic, gender, age, and class divides.

Known for his documentary work with indigenous communities, memory, and human rights, Julio Pantoja, through his photographs, plays with the edge created by the contrast between Chambi’s Cusco and ours. As I argued above, Chambi’s vision was bi-focal, his gaze undeflected. That same bi-focality is at work in Pantoja’s photographs; indeed, the series of photographs he took of the exhibit and people’s reactions to it seem almost like trompe l’oeils where the past irrupts in the present allowing both to be seen simultaneously as we had hoped.

Photo: Julio Pantoja, 2014.

Photo: Julio Pantoja, 2014.

Photo: Julio Pantoja, 2014.

Photo: Julio Pantoja, 2014.

Photo: Julio Pantoja, 2014.

Photo: Julio Pantoja, 2014.

Photo: Julio Pantoja, 2014.

Indeed, Pantoja’s photographs intervene in the exhibit in subtle yet important ways. They either create an edge as Chambi’s luminous black and white takes contrast with the color, bustle, and pollution of the city today, or they blend that edge and become almost indistinguishable from Chambi’s when the color is muted. We see this technique in the last image above where the two boys almost become part of the city today. It is only upon a second viewing that the viewer realizes that the past and the present are confronting one another in his photographs. In this way, Pantoja brilliantly managed to reproduce the little shocks that viewers repeatedly experienced during the month the exhibition was up.

Pantoja’s concern with historical memory and indigenous culture also came into play as he highlighted not only the interruptions created by the exhibit, but also the continuities between the past and the present. In the three days that he spent in the city, he managed to capture a chichera carrying her plastic bucket full of chicha marching right underneath Chambi’s famous image of a well-to-do chichera. A personal friend of his, Chambi had photographed her through the years. Her pose clearly reflects her important status in Cusco during Chambi’s time, while the chichera walking by underneath her has become yet another street vendor in the city.

While Julio Pantoja played with the edge between past and present, onlookers tended to intervene in the exhibit in other ways. Many took photos on their cell phones; others posed, peering behind the installations as if emerging from the past but in full color.

Photo: Julio Pantoja, 2014.

Photo: Julio Pantoja, 2014.

Photo: Julio Pantoja, 2014.

Photo: Julio Pantoja, 2014.

Photo: Julio Pantoja, 2014.

The dimensions of learning that emerged from the exhibition came fully into focus only months after it came down. At the time we planned it, as I mentioned above, we jokingly referred to our plan as wanting to create a monumental event for a monumental city. What we neither envisioned nor anticipated was the profound effect that the exhibition would actually have on the city and its inhabitants. Onlookers talked to one another, comparing notes as to what had changed and asking older Cusqueños about the images. The many young kids, adolescents, and immigrants that stood before the images had no memory of the city Chambi had photographed and began to ask their elders and families for information. Indeed, I was surprised time after time by people’s enthusiasm, and I repeatedly encouraged them to pinpoint the source of their excitement. Conversations spontaneously took place in front of the images as people attempted to flesh out the contrast between the past and present and turned to one another in search of clues. I asked myself: why was it so important for them to establish the exact location of the images? Why the urge to puzzle together the exact nature of the changes in the streets, where a balcony had been taken down and what had replaced it, and so on? It seemed as if Cusqueños were rediscovering their city. This dialogue took place throughout the city on a daily basis for the entire month and beyond it. Incessantly.

Most photography exhibitions that aim to be public tend to be out of reach. Not being in a museum is not enough for art to be public.

During the time the exhibition was up, I was repeatedly taken aback to find how, time and again, people either asked outright who Chambi was or seemed proud to have learned of such a great and famous Cusqueño. Indeed, while Latin Americanists and photographers almost everywhere know Chambi’s work, even Japanese tourists, to their great delight, recognized his photographs. In the city to which he had devoted his life, he remained a well-guarded treasure. The extent to which this was so had become apparent to me when Teo and I went to talk to the mayor to get his support for the exhibition and, upon leaving, were given an expensive volume that the administration had published highlighting the magic of the city. As we left, Teo, otherwise so diplomatic, dismissively referred to the book as “useless” as he chucked it onto the back seat of his car. The glossy volume highlights the city’s history, churches, rituals, luminaries, and artists in full page photographs as is typical of such publications. However, in the section devoted to the city’s photographers, Chambi was glaringly absent. Instead, his other contemporary Eulogio Nishiyama was featured, along with contemporary photographers. The glaring absence of Chambi, I suspected, was what had pained Teo. Paradoxically, this was partially the result of the shroud of secrecy that he had created to protect the archive from theft, even as he devoted his efforts to making Chambi an internationally known figure.

While we had managed to hold Chambi up to the city, the importance of putting the enlargements within arm’s reach on city streets, which had only been an intuition, proved to be the crucial element with respect to public art. Most photography exhibitions that aim to be public tend to be out of reach. Not being in a museum is not enough for art to be public. And in museums, which are typically still largely viewed as temples of culture, little to no conversation takes place. Instead, guides talk, leading, informing, teaching, and thus accentuating the top-down nature of most exhibitions. The conversations that people were having in front of the images in Cusco, often with total strangers—across class, age, and ethnic divides—seldom take place in a museum or gallery setting, and much less become a city-wide dialogue. It was the exhibit’s most important effect, and it made us realize what we had accomplished.

If I had any doubts before, this experience brought home to me the importance of public art and what a truly public exhibit can achieve. In “El Cusco de Martín Chambi,” with few exceptions, we managed to put the images within arm’s reach of thousands of people. Thus, while collaboration in the preservation of archives is key, it is also important to find ways of making an archive’s holdings accessible to the larger public. This counters an archive’s natural tendency to preserve and protect rather than share and exhibit. It was a great coup, then, to get director Teo to agree to make so many of his grandfather’s images public. At the same time, well over 7,000 previously unknown glass plates were scanned and catalogued at the time.

While the moments captured by photography are ephemeral and the era of the great glass plate photography is long over, the images captured by photographers like Chambi gain greater currency with the passage of time. The high quality and resolution of the photographs he took of Cusco became evident to all who paused before our exhibit. It brought an era, a culture, and a people into focus and provided a welcome and necessary contrast to our time. As I witnessed the population’s embrace of the exhibit and their enthusiasm, I became ever more convinced of the archive’s immense value to all of us and the urgency of preserving it. The exhibit interrupted the flow of pedestrians, the past irrupted in the present, and people stopped and talked across class, race, and gender divides. These are all necessary conversations and precious ephemeral moments like photography itself.